Click here for a PDF version of our full comments on Kentucky’s 1115 Medicaid Waiver Request.

Since 2016, Kentucky has been attempting to make changes to its Medicaid program that would erect barriers to coverage and roll back important health benefits. As an organization concerned with the well-being of all Kentuckians, the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy (KCEP) has opposed these changes for the harm they would do to financial security, health and the economy.1 Following a court order to send the waiver request back to the Department for Health and Human Services (HHS) for further review, HHS decided to open a new comment period on the waiver as approved in January of 2018. The following comments build on KCEP’s previous comments and speak directly to the concerns of the federal court ruling: namely that the proposed changes contradict the purpose of the Medicaid program, which is to provide health coverage to those who cannot afford it. The waiver would result in unacceptable coverage losses, and therefore should be rejected.

Kentucky’s Medicaid Waiver Works Against the Objective of Medicaid

Having Medicaid coverage means that low-income Kentuckians can get care when they need it so they can get and stay healthy. Though health is a byproduct of usable, affordable coverage — and Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion is already demonstrating health gains in the state — it is not the purpose of Medicaid. As federal law sets out and Stewart v. Azar affirmed, the purpose of Medicaid is to furnish medical assistance to low-income populations identified by Congress. In the words of Judge Boasberg:

“The Medicaid program was created… for the purpose of providing federal assistance to States that choose to reimburse certain costs of medical treatment for needy persons…” Through the [Affordable Care Act] ACA, Congress made Medicaid an “element of a comprehensive national plan to provide universal health coverage.” As amended, one objective of Medicaid thus became ‘furnishing… medical assistance’ for this new group of low-income individuals.2

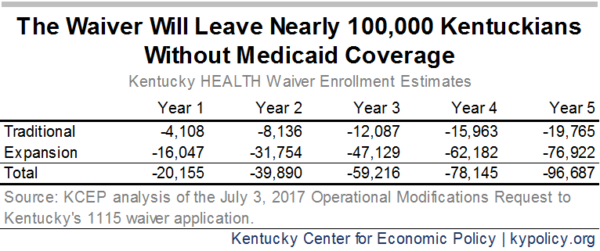

Medicaid as a tool for providing medical assistance is highly effective; any changes to the program should be aimed at improving on that effectiveness. Far from achieving the primary objective of Medicaid, however, Kentucky’s 1115 waiver request creates multiple tripwires that will result in at least 100,000 people losing health coverage. Since we should not expect they will become insured by other means, the waiver will undo much of the historic gains in coverage we have experienced over the past several years. It is for this reason that the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) should reject Kentucky’s Medicaid waiver.

Kentucky’s Medicaid Expansion Led to Unprecedented Gains in Coverage and Care

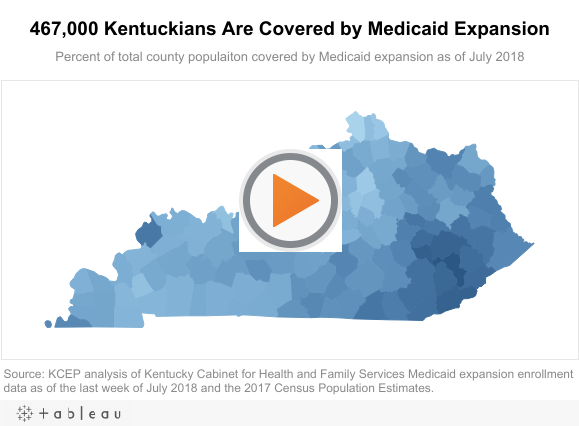

Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion has been an incredibly successful tool in providing medical coverage to Kentuckians as envisioned under the Affordable Care Act. At its peak, Medicaid expansion covered over half a million low-income Kentucky adults, and as of July, it covered 467,000.

Medicaid expansion is the primary reason Kentucky’s rate of uninsured dropped so precipitously in recent years. Between 2013 and 2016, Kentucky’s uninsured rate fell from 14.9 percent to 5.5 percent. Research shows this historically large reduction in the uninsured was even more dramatic in Kentucky zip codes with especially high poverty rates. The same research showed that these geographically-based disparities were also reduced for those forgoing care because of cost, having no regular source of care and already having (reporting) excellent health, all of which improved in Kentucky.3

Under this unprecedented expansion of coverage, more Kentuckians received medical care and that care has already begun to improve the quality of life and economic security across the commonwealth. According to the most recent assessment of low-income adults in Kentucky and Arkansas, which also expanded Medicaid, compared to Texas, which did not, having and using a primary care doctor, getting check-ups and getting glucose checks all increased for adults in the expansion states. At the same time, skipping medications or delaying care due to cost, using the ER as a usual source of care, having difficulty paying medical bills and out of pocket medical spending all decreased among Medicaid-eligible adults who lived in the expansion states. Perhaps most striking for low-income adults in Kentucky and Arkansas was a five percentage point increase in those who reported excellent health and a commensurate decrease in fair or poor health.4

Barriers to Coverage Would Reduce Medicaid Enrollment

Under Kentucky’s proposed waiver, there are multiple new ways a Medicaid enrollee could lose coverage by having their coverage suspended, being locked out for six months or eventually getting disenrolled from Medicaid altogether. Coverage losses would happen if a Medicaid enrollee who is expansion eligible or if some low-income parents did any of the following:

- Did not pay premiums after a 60-day period and have earnings above the poverty line.

- Failed to comply with the annual redetermination process in a timely manner.

- Did not report a change in income, family size or work hours that led to a month of coverage for which they were not eligible.

- Worked or volunteered less than 80 hours in a month.

- Voluntarily withdrew from Medicaid coverage, even while eligible.

Collectively, these new barriers to coverage would lead to 96,700 Kentuckians losing coverage, on average, according to the latest estimates from the state found in the Operational Modifications Request.5 In an amicus brief to Stewart v. Azar, 43 public health experts and 8 medical school deans estimated the enrollment losses to be much higher: 175,000 to 297,000.

While there are some ways for enrollees to regain coverage (for example by back-paying missed premiums, catching up on work hours or taking a health or financial literacy class), at a minimum, the churn of enrollment and disenrollment will dramatically rise. Kentucky already suffers from high rates of cancer, diabetes and substance use disorders, so even short periods of coverage loss can disrupt life-saving medical care or lead to serious financial hardship.

Paperwork and Red Tape Will Account for Much of Enrollment Loss

Many people will have their coverage and care disrupted or cut off, not because of a failure to meet the requirements, but due to a failure in correctly managing all of the paperwork involved. In an estimate from the Kaiser Family Foundation, paperwork errors and lack of reporting accounted for 62 percent of those they estimate would lose coverage.6

It is easy to understand how confusion would lead to disenrollment. Medicaid enrollees will have to track and routinely report on monthly income, hours worked and family size. They will also have to know when their redetermination date is, and promptly complete that process before the window closes. Disabled or ill Medicaid enrollees will need to be aware of their ability to apply for a strict medical frailty determination or a good cause exemption, and be able to submit their application, or their lack of work due to that illness or disability could erroneously lead to disenrollment.7

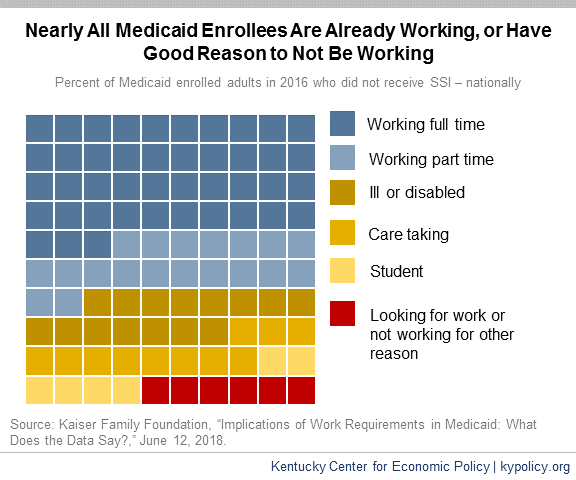

Taking Away Coverage for Failure to Meet New Work Requirements Will Harm People Who Already Work

In Kentucky, the majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees currently work, and four out of five adult Medicaid expansion enrollees worked at some point in the past five years. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 62 percent of Kentucky Medicaid-covered adults currently work, and 74 percent come from working families. Of the working Kentucky Medicaid enrollees, 77 percent are working full time (at least 35 hours per week) and 23 percent are working part time. Importantly, most all of those who do not work are ill or disabled, caretaking, studying, retired or looking for work. Nationally, only 1.3 percent of Medicaid adults do not fit into those categories.8

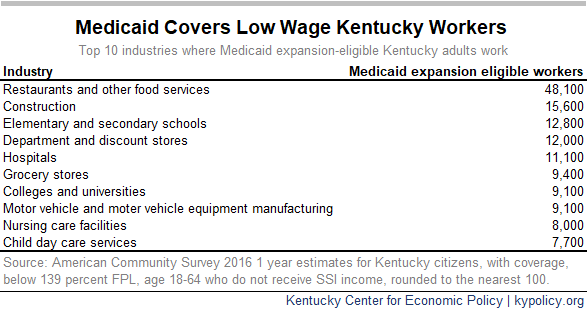

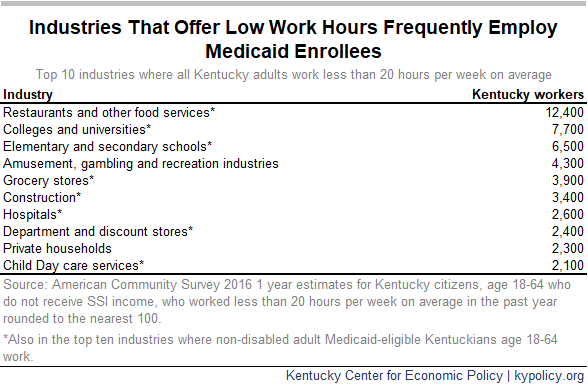

Many workers qualify for Medicaid because they are employed in low wage jobs where health coverage is unavailable or unaffordable. Workers must earn at or below 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) to qualify, which amounts to roughly $16,750 for an individual and $34,650 for a family of 4. Medicaid enrollees who work do so in industries like restaurants, construction, groceries and many retail industries where the structure of employment creates risk for coverage loss under this waiver.

Many of these industries have notoriously poor scheduling practices that make it difficult to keep a regular schedule from week to week, including:

- Little to no advance notice of weekly shifts.

- Being sent home early or unexpectedly called in the same day as a shift, known as “just-in-time” scheduling.

- Split shifts or on-call shifts.9

In addition to poor scheduling practices, these industries are among those most often hiring workers for less than 20 hours a week (a close approximation to the 80 hours per month Medicaid requirement). In fact, of the top 10 industries where Medicaid-eligible Kentuckians work, 8 are also in the top 10 industries that most employ Kentucky workers for less than 20 hours a week on average. For many workers covered by Medicaid, the option to work full time is not offered to them by their employers. Many industries restrict the number of hours they give to their employees so they do not have to provide benefits or other costs of employment associated with full-time labor.

Not getting enough hours at work is a problem throughout the U.S.; low-income workers often are forced to work fewer hours than they would prefer. According to the Current Population Survey conducted by the Department of Labor, over five million Americans work part time involuntarily and would work more if their employer offered more hours or they could find full-time jobs. In Kentucky, 13.5 percent of part-time workers are involuntarily part time, a number that rose as high as 23.2 percent during the heart of the Great Recession in 2009.10

Evidence from the second month of Arkansas’ Medicaid work requirement also makes clear that work and reporting requirements would reduce enrollment in Kentucky. In the second round of reporting, 15,137 Arkansans were required to report on their work activity. Of those, 12,587 people, or 83 percent failed to report anything. Of that group, 5,426 now have “two strikes,” and if they fail to report again this month will be locked-out of Medicaid and will not be able to re-enroll till 2019. Another 10.4 percent reported some kind of an exemption, but it is not clear either what those exemptions were or if the state approved all of them.

Just 844 people, or 5.6 percent, actually satisfied the requirement to report work activities such as a job, volunteering, job searching or fulfilling the SNAP requirement. Among the Arkansans who told the state government what they did that month, 639 simply stated they were meeting the SNAP requirement. Only 145 of the 15,137 actually reported that they worked enough hours that month to satisfy the requirement.11 Kentucky’s work requirement is far more complex and will require more reporting from participants. It is likely, then, that many will fail to meet the requirements and lose their Medicaid coverage.

Taking Away Coverage for Failure to Meet New Work Requirements Will Not Improve Employment

Evidence from over 20 years of work requirements in other programs including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) shows they do not succeed in the goals of promoting long-term employment or reducing poverty. In fact, studies that tracked cash assistance participants subject to a work requirement found that:

- Gains in employment were modest and faded over time.

- Most participants had unstable employment for years after they were subject to the requirement.

- Most participants stayed poor, and some became poorer.12

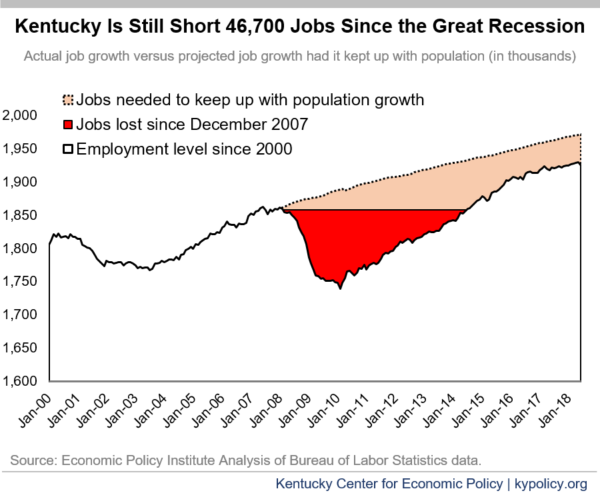

One explanation for a lack of improvement in employment as a result of work requirements is the difficulty of finding better-paying jobs than the ones Medicaid enrollees already have. Lack of available jobs in parts of Kentucky, especially in distressed rural areas, makes finding work, much less higher-quality work, a struggle for many. The Department of Labor has identified 51 Labor Surplus Areas in Kentucky, areas where there are more people looking for work than there are available jobs.13 Kentucky has 22 counties where the unemployment rate is above 7 percent, and 43 counties that face persistent poverty (where at least 20 percent of the population has lived below the poverty line for the past 30 years). Most of these counties are in the eastern part of the state, which has experienced structural economic distress for decades.14 Statewide, if job growth had kept up with population growth since the recession, Kentucky would have 46,700 more jobs – an aggregate measure of the additional slack we have in our economy compared to before the Great Recession.

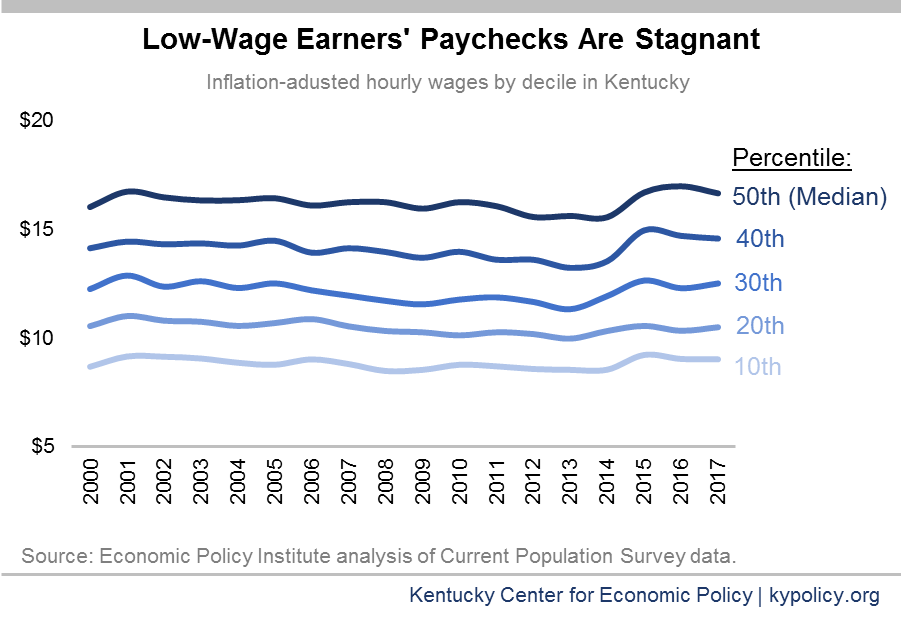

Real wages for those who earn at or below Kentucky’s median income have remained stagnant for the last several decades, further compounding the difficulty Kentuckians face when trying to make ends meet and afford health coverage. This long-term wage stagnation makes it even harder to believe that by punitively threatening coverage, low-wage workers could simply earn more money, or find better paying jobs in parts of the state where they are scarce.

Premiums Will Reduce Medicaid Coverage

Kentucky’s plan to charge premiums as a condition of coverage for Medicaid ignores other states’ experience with premiums. There is a wide body of research that shows even small premiums or co-pays reduce enrollment and limit access to care.15

Specific state examples help to illustrate this effect. Oregon received approval in 2003 to increase the premiums it charged participants in its Medicaid waiver program and also impose a six month lock-out period for non-payment of premiums. Following these changes, enrollment in the program dropped by almost half.16 Similar effects occurred with programs in Utah, Washington and Wisconsin.17 All five states that have instituted premiums for their expansion populations have seen either an increase in collectable debt among enrollees, a decrease in enrollment or at the very least an increase in churn in and out of the Medicaid program.18

The most recent example is Indiana. There Medicaid enrollees must make a mandatory contribution to a POWER Account (essentially a premium), and if an enrollee above the poverty line misses a contribution he or she will lose coverage. During the first 21 months of the program, 55 percent of all Medicaid enrollees missed one such contribution, and nearly 60,000 were either disenrolled or never enrolled. Of those who were never enrolled, 22 percent said they couldn’t afford the premium and 22 percent said they were confused by the payment process. Of those who were kicked off, 44 percent said they couldn’t afford the contribution and 17 percent said they were confused by the process.19

Special Populations Are Put at Risk by Barriers to Coverage

Children – It is estimated that when states expanded Medicaid, 710,000 children across the country who were already eligible gained coverage as well, a phenomenon known as the “welcome mat” effect. Conversely, the same researchers estimate that 200,000 eligible children remain uninsured in states that did not expand Medicaid.20 There is risk that when parents lose coverage under this waiver, kids may eventually go without coverage as well when it comes time to re-verify eligibility or after a family moves. It is even more likely that newly eligible children will not get covered as their parents succumb to an “unwelcome mat” effect. In addition to the obvious advantages for children of coverage across the household, children who live in homes where parents are healthy have better cognitive and social development outcomes.21

Kentuckians with Disabilities – According to American Community Survey data, over a quarter of insured Medicaid expansion eligible adults have some kind of disability and do not receive income from Supplemental Security Income (SSI). One study showed 72 percent of Kentucky’s population of Medicaid expansion-eligible adults have one or more chronic conditions.22 Although there is a “medically frail” designation and an exemption for those with SSI or Social Security Disability Insurance, there are many Kentuckians covered by Medicaid expansion who will not meet these criteria, but still have conditions that make it hard or impossible to routinely meet the 80 hours of work or volunteer activity required to keep coverage. Indeed, adults with disabilities who are covered by Medicaid are already likelier to be unemployed, work sporadically, and or work less than full time, making it harder to comply with the work requirement.23

Kentuckians Struggling with Substance Use Disorders – Although the medically frail designation technically includes “chronic substance use disorders (SUD),” that designation requires a long-term history of substance use with a record of medical claims. Many people with addiction problems will not meet these criteria; some may never have received treatment including because they were wary of making their condition known due to its illicit nature or, they are newly addicted. These individuals will not have any kind of exemption available to them until they enter treatment of some kind, but their addiction will increase the odds they will not meet the work requirement and thus lose the coverage needed to access treatment.24 Finally, many with SUDs have a criminal record due to their use of illicit drugs, which creates a structural disadvantage when it comes to seeking employment. There is no accommodation in Kentucky’s work requirement for people with criminal records and many people who cannot pass background checks will likely lose coverage because they find it difficult to secure employment or volunteer opportunities.

Those Kicked Off Medicaid Would Likely Remain Uninsured

It is highly improbable that Kentuckians who will lose coverage due to provisions in this waiver will be able to either gain coverage from their employers or see their incomes rise such that they can afford to purchase insurance elsewhere.

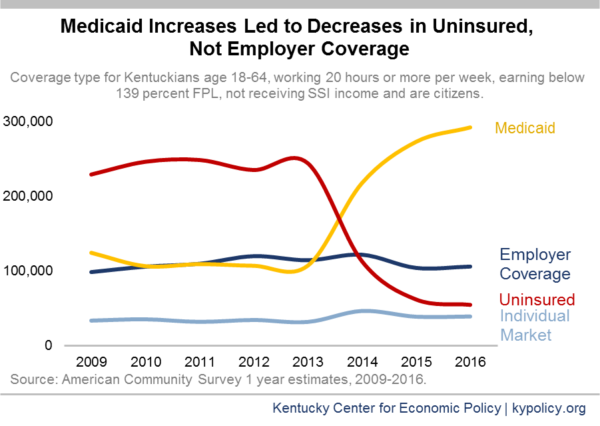

As previously noted, the uninsured rate plummeted in Kentucky after Medicaid eligibility was expanded to all non-elderly Kentuckians up to 138 percent FPL. Little changed in employer coverage or individual coverage after expansion was enacted, suggesting that most Kentuckians newly enrolled in Medicaid were previously not covered elsewhere. It follows then that Medicaid fills a need that employer-based and individual coverage has not and will not address.

Evidence from other states also suggests that many Medicaid expansion enrollees lacked viable private coverage options. In Ohio, for instance, 75 percent of Medicaid expansion enrollees did not have insurance prior to 2014.25 Evidence from Indiana’s mandatory POWER Account contributions shows that less than half of those who were kicked-off coverage or who were never covered due to non-payment were able to get insured afterward. And in Tennessee, when 170,000 adults were disenrolled from Medicaid, the uninsured rate increased by 5 percentage points more than other southern states, health care utilization noticeably fell, and the use of free and public health clinics rose.26 It follows that if the requirements in the waiver result in 97,000 people without coverage, a substantial percentage will not have coverage of any kind.

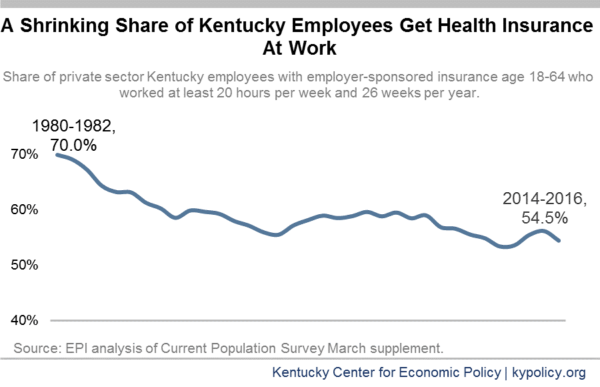

The long-term trend of erosion in employer coverage underscores the concern that Medicaid enrollees will be unlikely to find coverage elsewhere. In 1980, 70 percent of Kentucky private sector employees received health coverage through their job; by 2016, that number was down to 54.5 percent.

Low-wage workers, covered now under Medicaid expansion, are even less likely to have jobs where employers offer coverage. According to national Bureau of Labor Statistics data, only 37 percent of workers at the bottom quartile of earners were employed at a firm that provided health insurance to their employees, and less than a quarter actually get coverage through work.27

In addition, many businesses require employees to work a certain number of hours per week or to have been on the job for a certain number of months before they qualify for benefits. An Urban Institute study recently found that, for part-time employees in Kentucky firms that hire low wage workers, only four percent of employees were eligible for employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). The study also found that the average annual employee contribution for health insurance in Kentucky was $1,453. For a full-time minimum wage worker this constitutes 11 percent of annual income, far exceeding the insurance affordability benchmark set forth in the ACA of 2 percent of annual income for people at 100 percent of the poverty level.28

When Medicaid enrollees below the poverty line lose coverage for failure to report or meet the required number of hours of work activity, they will also not have access to premium subsidies on the marketplace. This means that a single Kentuckian earning wages at the poverty level (just over $1,010 per month) would have to pay an average monthly premium of $422 per month, or 41.7 percent of his or her total income.29

Kentuckians losing Medicaid coverage and earning between 100 percent of the poverty level and 138 percent ($1,396 per month) would also be ineligible for premium tax credits. This is because marketplace premium assistance is contingent upon individuals not being offered “minimum essential coverage” elsewhere, which, though not in compliance with waiver requirements, they would still be technically offered through Medicaid.

CMS Should Reject Kentucky’s Barriers to Coverage

Kentucky has benefitted greatly from Medicaid expansion. State officials and CMS should work to build on these historic, nation-leading coverage gains and provide more avenues for Kentuckians to get and use health care. But the proposed changes in the waiver work against the goal of “furnishing medical assistance,” the primary objective of the Medicaid program. Instead the changes will swell Kentucky’s ranks of uninsured, taking Medicaid coverage from tens of thousands and leaving them without coverage of any kind. It is for these reasons we urge CMS to reject Kentucky’s request, thereby protecting coverage in the commonwealth.

- Dustin Pugel and Jason Bailey, “Proposed Medicaid Waiver Would Reduce Coverage and Move Kentucky Backward on Health Progress,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Oct. 7, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/1115-Medicaid-Waiver-Federal-Comments-KCEP.pdf. ↩

- Stewart v. Azar, Civil Action No. 18-152 (JEB), June 29, 2018, https://ecf.dcd.uscourts.gov/cgi-bin/show_public_doc?2018cv0152-74. ↩

- Joseph Benitez, “Did Health Care Reform Help Kentucky Address Disparities in Coverage and Access to Care among the Poor?” Health Services Research (June 2018), pp. 1387-1406. ↩

- Benjamin Sommers, “Three-Year Impacts of the Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care and Health Among Low-Income Adults,” Health Affairs published online, May 17, 2017, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0293. ↩

- Office of the Governor, “Kentucky Health 1115 Demonstration Modification Request,” July 3, 2017, https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dms/Documents/ProposedOperationalModificationstoWaiverApplication.pdf. ↩

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz and MaryBeth Musumeci, “Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 27, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/implications-of-a-medicaid-work-requirement-national-estimates-of-potential-coverage-losses/. ↩

- Margot Sanger-Katz, “Hate Paperwork? Medicaid Recipients Will Be Drowning In It,” The New York Times, Jan. 18, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/upshot/medicaid-enrollment-obstacles-kentucky-work-requirement.html?rref=collection%2Fbyline%2Fmargot-sanger-katz&action=click&contentCollection=undefined®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection. ↩

- Rachel Garfield and Robin Rudowitz, “Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Jan. 5, 2018, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Understanding-the-Intersection-of-Medicaid-and-Work. ↩

- Jessica Gehr, “Doubling Down: How Work Requirements in Public Benefit Programs Hurt Low-Wage Workers,” Center for Law and Social Policy, June 2017, http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Doubling-Down-How-Work-Requirements-in-Public-Benefit-Programs-Hurt-Low-Wage-Workers.pdf. ↩

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data. ↩

- Arkansas Department of Human Services, “Arkansas Works Program July 2018 Report,” August, 2018. ↩

- LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 7, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty-evidence-shows. ↩

- United States Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, “Labor Surplus Area, Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Labor Surplus Areas (LSA),” https://www.doleta.gov/programs/lsa.cfm. ↩

- Nathan Joo and Elaine Waxman, “How Kentucky’s Economic Realities Pose a Challenge for Work Requirements,” Urban Institute, Aug. 9, 2018, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-kentuckys-economic-realities-pose-challenge-work-requirements. ↩

- Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri and Julia Zur, “The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 1, 2017, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/. ↩

- Jessica Schubel and Jesse Cross-Call, “Indiana’s Medicaid Expansion Waiver Proposal Needs Significant Revision,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 17, 2014, http://www.cbpp.org/research/indianas-medicaid-expansion-waiver-proposal-needs-significant-revision. ↩

- Ashley Spalding, “Indiana Approach to Medicaid Expansion Limits Access to Needed Care,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 26, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/indiana-approach-to-medicaid-expansion-limits-access-to-needed-care/. ↩

- Andrea Callow, “Charging Medicaid Premiums Hurts Patients and State Budgets,” Families USA, April 2016, http://familiesusa.org/product/charging-medicaid-premiums-hurts-patients-and-state-budgets. ↩

- Lewin Group, “Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0: POWER Account Contribution Assessment,” March 31, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support-20-POWER-acct-cont-assesmnt-03312017.pdf. ↩

- Julie Hudson and Asako Moriya, “Medicaid Expansion for Adults Had Measurable ‘Welcome Mat’ Effects On Their Children,” Health Affairs, September 2017, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0347. ↩

- “Harm to Children From Taking Away Medicaid From People for Not Meeting Work Requirements,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 11, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/how-medicaid-work-requirements-will-harm-children. ↩

- Sommers, “Three-Year Impacts of the Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care and Health Among Low-Income Adults,” 2017. ↩

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Harm to People With Disabilities and Serious Illnesses From Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements,” Jan. 26, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/how-medicaid-work-requirements-will-harm-people-with-disabilities-and-serious. ↩

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Harm to People With Substance Use Disorders From Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements,” May 9, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/harm-to-people-with-substance-use-disorders-from-taking-away-medicaid-for-not. ↩

- Barbara Sears, “Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Report to the Ohio General Assembly,” The Ohio Department of Medicaid, http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Annual/Group-VIII-Assessment.pdf. ↩

- Thomas DeLeire, “The Effect of Disenrollment from Medicaid on Employment, Insurance Coverage, Health and Health Care Utilization,” National Bureau of Economic Research published online, Aug. 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24899. ↩

- Aviva Aron-Dine, “Eligibility Restrictions in Recent Medicaid Waivers Would Cause Many Thousands of People to Become Uninsured,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Aug. 9, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/eligibility-restrictions-in-recent-medicaid-waivers-would-cause-many-thousands-of. ↩

- Anuj Gangopadhyaya, Emily Johnston, Genevieve Kenney and Stephen Zuckerman, “Kentucky Medicaid Work Requirements: What Are the Coverage Risks for Working Enrollees?” Urban Institute, Aug. 2018, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/kentucky-medicaid-work-requirements-what-are-coverage-risks-working-enrollees. ↩

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, “Marketplace Average Benchmark Premiums,” Accessed August 16, 2018, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-average-benchmark-premiums/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D#notes. ↩