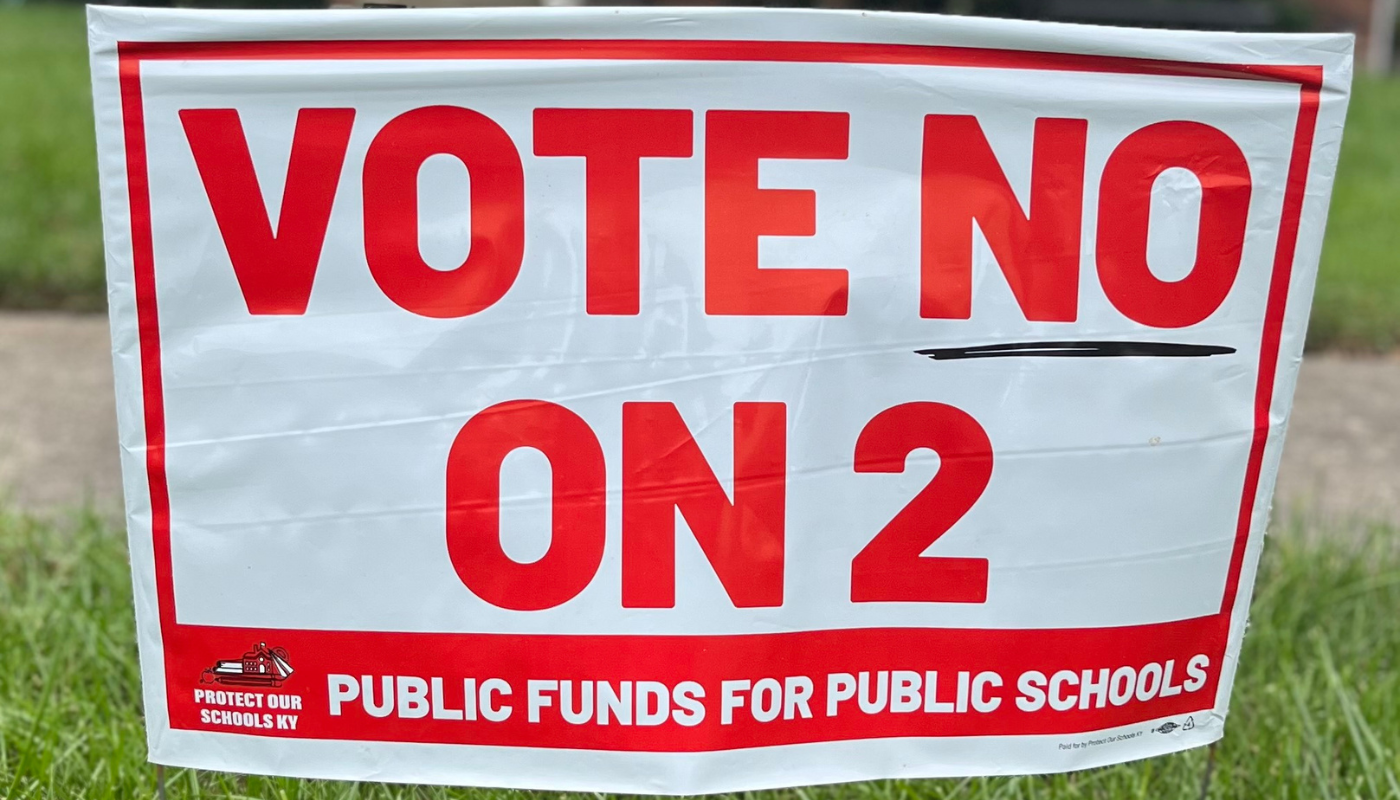

Despite the best efforts of anti-public school activists and the deep pockets of out-of-state billionaires, Kentucky voters resoundingly defeated the proposed constitutional amendment allowing public dollars to be diverted to private schools. The amendment was rejected in all 120 Kentucky counties and at the hands of a unique bipartisan coalition of rural, urban and suburban voters.

This decisive verdict takes private school vouchers off the table in Kentucky. And it sends a clear message to lawmakers about voters’ preferred approach to improving education: finally reinvest in our public schools after nearly 20 years of budget cuts.

But another current goal of the General Assembly stands in the way of fully realizing that vision. That’s the effort to eliminate the source of more than 40% of the state revenue that has funded our schools, the individual income tax.

Cutting the income tax has long been a target of some. For years, the idea was to do “tax reform,” which was defined as lowering the income tax and raising or broadening the sales tax to offset the revenue loss. That idea was regressive, shifting taxes from the wealthy to everyday working Kentuckians, and hardly went anywhere.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic led to inflation and resulted in federal stimulus legislation that spurred a fast economic recovery and a surge in tax revenue in nearly every state. Under the cover of a temporary boost in tax receipts, the General Assembly began cutting the income tax while not bothering with measures to replace the lost revenue.

They created a formula that reduced the income tax rate from 5% to 4.5% in 2023 and then to 4% in 2024. But now that the stimulus dollars are ending and the economy is somewhat softening, revenues are flat, income tax receipts are falling and trouble is on the horizon.

A new estimate from the Office of the State Budget Director projects total General Fund revenue will decline by $223 million this year compared to last year. A year-to-year drop in receipts has only happened three times in the last 50 years, and every other instance was during an economic recession.

On top of that, lawmakers are considering another cut in the individual income tax rate to 3.5% in the coming session, which would take effect in January of 2026. Legislative leaders say their formula makes that cut affordable, but the General Assembly moved the goalposts on its rules in the last session to make it appear to be the case.

Enacting another cut will make the top income tax rate 42% lower than it was from the years 1936 to 2018. Each half point cut in the income tax rate costs about $700 million a year. That’s equal to the current annual state funding for 81 school districts, or the cost of employing 5,782 Kentucky teachers and school employees. What if the legislature took that $700 million and reinvested it in public schools, rather than sending the bulk of it to Kentucky’s richest residents?

That reinvestment would be especially meaningful to the same rural communities that were an emphatic “no” on Amendment 2. Their school districts are heavily dependent on state revenue due to low local property wealth. And since incomes tend to be significantly lower in many rural counties, cuts to the income tax mean little to most of their residents’ wallets.

In a speech last summer, Speaker David Osborne cast doubt on the goal of getting the income tax down to zero. We need more of that kind of wise caution.

The education message from voters on election day this year was the same one they delivered to then-governor Matt Bevin in the 2019 election, who became highly unpopular after attacking teachers’ pensions and public school funding.

Kentuckians want their elected leaders to invest in their public schools and protect them. That takes money they cannot continue to give away.

This column was published in the Lexington Herald-Leader on Nov. 25 and the Courier Journal on Dec. 4.