For years, inadequate state funding for public education has forced Kentucky’s kids to make do with outdated textbooks and technology, deprived them of vital supports and left them without the attention and enrichment all students deserve.

But in the past several years, the federal government stepped up. Thanks to more than $3 billion in federal funding designed to accelerate academic recovery and meet other student needs in the post-pandemic period, school leaders were able to hire necessary staff and better meet student needs. It filled a gap left when the legislature mostly prioritized large budget surpluses and income tax cuts over restoring funding to public schools.

That federal funding, known as Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER), expires this fall, and superintendents across the commonwealth say students will be much worse off for it. In fact, national research shows Kentucky’s kids will be among the hardest hit in the nation because ESSER funds provided more support to schools with the greatest needs and Kentucky has one of the nation’s highest rates of high-poverty school districts.

Districts used these vital resources to adopt curriculum that addresses learning loss, hold summer programming for kids who need help catching up and provide tutoring. These needs existed before the pandemic and will continue long after. But without ESSER funds, important programs will end for many high-poverty districts, public education leaders told us.

“[The loss of ESSER funds] widens the gaps between ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ and widens the inequities,” said Superintendent Alvin Garrison of Covington Independent Schools.

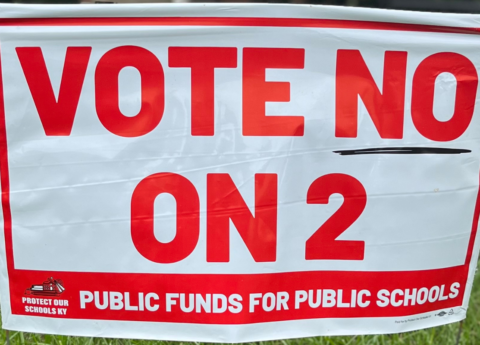

The challenge of this loss is sharpened by the potential to lose even more. This November, Kentuckians will vote on Amendment 2, which would allow diversion of public money to be spent on private school vouchers. If this voucher amendment passes, Kentucky’s public schools can expect to see their state funding deeply reduced, with the most harm falling on the highest-poverty rural districts.

On average, ESSER funding afforded school districts in Kentucky $1,421 per student annually to provide critical academic support, address social, emotional and mental health needs, promote physical safety and sustain school operations.

Johnson County Public Schools, in eastern Kentucky, spent the bulk of its ESSER funding on high-quality instructor resources for distance and online learning, as well as Chromebooks that the district couldn’t otherwise have afforded. Warren County Schools, in western Kentucky, used ESSER funds to double substitute teacher spending to at least temporarily address the extreme teacher shortage.

Rockcastle County, in central Kentucky, invested ESSER funds in student mental health positions that Superintendent Carrie Ballinger said were designed initially to be temporary. “But we have reached a point where there is absolutely no way we could operate without those employees,” she said.

As the ESSER funding cliff approaches, Kentucky school districts are inevitably needing to cut staff and scale back or eliminate services. And the need to make cuts is especially challenging in districts that used ESSER funds to add staff or maintain existing capacity. According to a recent survey by Kentucky’s Office of Educational Accountability, Kentucky superintendents plan to keep only 20% of newly created positions. In other words, 1,500 positions were expected to be eliminated as districts planned for the ESSER funding cliff.

ESSER funds provided a temporary glimpse of what is possible with additional resources to address both immediate and longstanding needs in Kentucky schools. But the end of those funds brings back severe funding challenges.

Additional state investment in K-12 funding is one way to mitigate the ESSER fiscal cliff, but the biennial budget passed by the Kentucky General Assembly earlier this year provided only modest funding for public schools. It was not enough to stabilize districts’ financial situations during the post-ESSER transition — despite extra revenue being available to do so.

One way Kentuckians can ensure that the post-ESSER loss isn’t made worse is to reject Amendment 2 this fall. Not only would that prevent the inevitable loss of public funding that would come with a private school voucher program, but it would send a message that lawmakers should put the focus back on Kentucky’s public schools, where the vast majority of students will always attend and where the needs are pressing and clear.

This column was published by the Lexington Herald Leader on Aug. 28, the Courier Journal on Sept. 3, and The State Journal on Sept. 5.