A proposal that could throw the country into chaos and jeopardize the U. S. Constitution is being pushed in states across the country this year, and in the Kentucky legislature as of Friday.

A growing number of states have petitioned Congress for a constitutional convention on a balanced budget amendment, and more legislatures are looking at the issue this year. Kentucky Senate President Robert Stivers filed the state’s version as Senate Joint Resolution 132.

If 34 states pass resolutions like SJR 132, Congress must call a convention under Article V of the U. S. Constitution. It would be the first constitutional convention since the founding meeting in 1787; all 27 prior amendments to the Constitution were enacted by the method of congressional passage followed by state ratification.

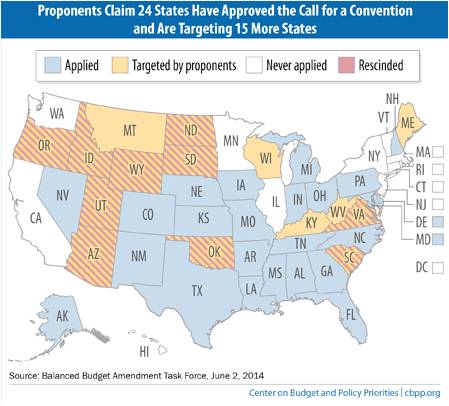

Proponents claim that 24 of the necessary 34 states already have live applications calling for a convention, and eight states have adopted resolutions just in the last four years: Alabama in 2011, New Hampshire in 2012, Ohio in 2013 and Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Michigan and Tennessee in 2014.

Advocates—led by big corporate interests like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) (see here and here) —are targeting about 15 states, including Kentucky. SJR 132 is drawn practically word-for-word from ALEC model language. As part of this campaign, Ohio Governor John Kasich has been touring states promoting the idea this year.

A convention could lead to extreme, wide-reaching and unpredictable changes to the U. S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, and the balanced budget amendment itself threatens to make economic downturns deeper and more painful while resulting in harmful cuts to the services on which Kentuckians rely.

States cannot control a constitutional convention

Although ALEC claims that the agenda of a constitutional convention could be controlled, experts say that conventioneers would have the power to alter anything and everything about the United States government—just as they did in the original 1787 constitutional convention when they threw out the Articles of Confederation and started over.

A convention would likely open up the Constitution to whatever amendments its delegates chose to put forward, regardless of its originally-stated purpose. Senate legislation accompanying the resolution in the General Assembly purports to control the actions of any Kentucky delegates to a convention, but it’s unlikely the courts would back the states in a conflict, experts say. Delegates to the 1787 convention ignored their state legislatures’ instructions, and delegates likely would be subject to federal, not state, law.

There are no safeguards to prevent a runaway convention that could lead to harmful changes to our founding document, as the Constitution itself puts no authority above a convention. And powerful interests are likely to be first in line to wield influence on who gets selected as delegates and what agenda gets considered. As former Chief Justice Warren Burger said:

“[T]here is no way to effectively limit or muzzle the actions of a Constitutional Convention. The Convention could make its own rules and set its own agenda. Congress might try to limit the convention to one amendment or one issue, but there is no way to assure that the Convention would obey.”

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia agrees, saying recently, “I certainly would not want a constitutional convention. Whoa! Who knows what would come of it?”

We also can’t depend on the state ratification process for amendments to protect the Constitution from radical changes. A convention could create a different method of ratification, such as a national referendum. The convention that crafted the U. S. Constitution ignored the ratification procedures under which it was established and created entirely new procedures.

Balanced budget amendment would cause great damage to the economy and basic services Kentuckians rely on

While the danger to the U. S. Constitution from uncontrolled changes is reason enough to reject this proposal, the risk of serious damage to the economy and the services that Kentuckians depend on from a balanced budget amendment is another reason to say no.

A balanced budget amendment would make recessions longer and more damaging by requiring deep budget cuts or tax increases when the economy weakens in order to make revenues equal expenditures. When recessions hit, spending for programs like food stamps and unemployment insurance automatically goes up as more people become eligible at the same time tax revenues decline. That’s how these programs are intended to work, helping limit the depth of recessions and hasten economic recovery by injecting dollars into the economy when they are needed.

But under a balanced budget amendment, Congress would have to cut such programs, increase taxes or both in the midst of recessions, making downturns longer and more severe. And by keeping Social Security from being able to draw monies from its trust fund (built up from revenues in prior years) to pay benefits without an offsetting surplus in the rest of the federal budget the same year, it could mean serious cuts to that program.

Proponents use false analogies when arguing for a balanced budget amendment, suggesting that states and families must balance their budgets each year. States must balance their operating budgets, but they borrow every year in their capital budgets to build infrastructure. They also spend money out of rainy day funds when times are tight. And families’ spending doesn’t equal their income; they borrow regularly to buy homes and send their kids to college, and spend out of savings such as for the down payment on a home.

Protecting U. S. Constitution and the economy of Kentucky requires rejecting proposal

A resolution calling for a constitutional convention on this issue last moved in 2011 in Kentucky, when it passed the Senate 22-16 but did not advance in the House. At the time, Speaker Greg Stumbo called it an “untested, untried and a very dangerous path to go down” that his chamber would pass “when pigs fly.”

Whatever its chances in Kentucky this year, there is big corporate money behind the call for a convention, movement on the issue across the country the last few years and a small number of additional state resolutions needed to make a convention happen. The implications for the country and its founding document are frightening. The Kentucky General Assembly must reject this proposal.