More than 488,000 women in Kentucky are raising an estimated 919,711 children under the age of 18. These biological, step, adopted and foster moms, grandmothers and other relatives and their children would benefit from policies that better support employment, job quality and economic security for Kentucky women.

Supporting Pregnant and New Moms at Work

Pregnancy and childbirth are a normal part of life for women: national data show that more than four out of five become mothers. An estimated 55,759 Kentucky women gave birth over the last year, 63 percent of whom were in the labor force. That’s 10 percentage points higher than the labor force participation rate for all women (53 percent in 2016), reflecting the necessity in today’s economy for many married and single moms to work. To promote economic security for expectant and new moms, healthy families and a productive workforce, Kentucky needs policies that incorporate these facts of life into employment practices:

- Pregnant workers rights: Today, some Kentucky mothers whose employers don’t provide pregnancy accommodations are forced to choose between getting paid or staying safe and healthy on the job. Legislation requiring employers to provide “reasonable accommodations” like temporary light duty and time and space to express breastmilk — so long as it does not impose an undue burden on the employer — can help moms continue working through pregnancy. Employers benefit from reduced turnover and increased productivity, and states benefit by reducing costs associated with public assistance when moms are forced to lose work. Bills were filed to address this issue in both the House and Senate in the 2017 session of Kentucky’s General Assembly, but neither were given a hearing.

- Paid parental leave: Many new moms without the option of paid leave must choose between coming back to work earlier than is best or losing income. Paid parental leave is a commonsense policy that supports families’ economic security and health as they welcome new members and promotes labor market attachment, job satisfaction and productivity. The U.S. is behind the rest of the developed world in providing paid leave, and Kentucky should become one of the handful of states leading the charge. House Bill 303 in the 2017 session, which was not given a hearing, proposed to give access to six weeks of paid maternity leave to women who have been employed for at least a year by firms with more than 50 employees. Parental leave should include fathers as well.

These policy improvements would especially help women working in low-wage jobs where employers are less likely to offer accommodations and paid leave. Furthermore, because mothers are more likely than fathers to experience hiring discrimination, supporting their attachment to work through pregnancy and babies’ first months is especially crucial for families’ economic security.

Work and Care Supports

At 53 percent, women’s labor force participation has not recovered from the last two economic recessions (it was 58 percent in 2000), but has grown overall in recent decades from 48 percent in 1979. In contrast, men’s participation has declined from 77 percent in 1979 to 63 percent in 2016. More women are working as a result of changing gender roles, a lack of adequate job opportunities for men and stagnant wages and incomes for all but the wealthiest Kentuckians in recent decades — meaning more women are working out of necessity. For moms and dads to be able to work, high-quality, reliable care for their children is essential.

- Child care assistance for low-income families helps make work a net economic benefit by making care more affordable. In 2016, Kentucky legislators gave a much-needed increase to the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) income threshold, from 150 percent of the 2011 poverty line to 160 percent of the 2016 FPL. However, CCAP reimbursement rates to providers are low and parent copayments are high, meaning that child care quality, availability and affordability are limited. In the 2018 session of the General Assembly, legislators should improve CCAP, including by appropriating more dollars to the program in the next state budget.

- Paid sick and family leave can help parents weather illness, care for sick kids and meet other care needs without losing employment or income. Only a handful of states have enacted paid sick leave.

- Healthcare is essential for moms’ and families’ economic security and health. Threats to coverage from the recently House-passed American Health Care Act and the state waivers it would encourage span across pregnancy, birth, family planning and women’s long-term health and affects those receiving coverage through Medicaid as well as private insurance. Federal and state lawmakers should build on strengths of the Affordable Care Act and reject proposals to reduce coverage, including for Kentucky moms.

- Kinship Care is another program improving care options and economic security for Kentucky families. The program provides a stipend of $300 a month for low-income grandparents and other relatives raising children, but was closed to new enrollees in 2013 due to state budget cuts. According to Census data, more than 99,000 Kentucky kids are being raised by a grandmother or other female relative, either in a married or single, female-headed household. The share of Kentucky kids being raised by relatives has increased in recent years, and state support for these caregivers should rise accordingly.

Equal Pay, Better Pay

Supporting work through pregnancy, after childbirth and alongside ongoing childcare needs is essential, but making work pay is the other side of the coin. Kentucky mothers face a lack of pay equity between women and men as well as a lack of job quality for all Kentucky workers.

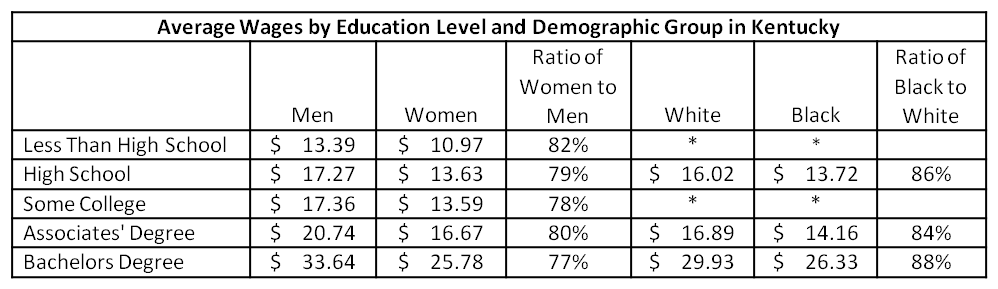

In 2016, Kentucky women making median wages brought home $15.64 an hour, just 88 cents on the dollar that men made ($17.84). Thanks to rising wages for women over time – but also due to eroding wages for men – the wage gap has shrunk: a decade ago women made 82 cents on the dollar men made and 20 years ago, 74 cents. Wide gaps persist when education levels are held constant, reflecting the fact that discrimination and undervaluing women’s contributions to the economy still play a big role. For example, as shown in the table below, women in Kentucky with an associates’ degree make $16.67 an hour on average compared to $20.74 for men (80 cents on the dollar). The data also shows that black Kentuckians make less than white Kentuckians. Though data limitations preclude an analysis of the wage gap by gender and race, it is fair to deduce that African American women face an even wider wage gap than white women.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Census data (CPS 2013-2016).

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Census data (CPS 2013-2016).

*Note: Sample size insufficient to produce estimate.

In addition to facing a gender wage gap, women are hurt by the same policies that hold down job quality for all Kentuckians. The Economic Policy Institute’s “Family Budget Calculator” estimates that a family of two (one adult, one child) living in Lexington, Kentucky, needs $42,004 a year to pay for housing, food, childcare, transportation, health care, taxes and other necessities. But at $15.64 an hour, a woman working full-time year-round for median wages brings home just $32,531.

Low pay means it is especially difficult for single female-headed households to make ends meet. More than half (55 percent) of Kentucky kids living with a single mom are in poverty, compared to one in four (26 percent) of all Kentucky kids.

The 2017 session of the General Assembly was a step backwards for job quality, with many bills passed that harm working moms. Kentucky legislators can reduce pay disparities and improve job quality in 2018, including by passing proposals that were filed in 2017 but never saw the light of day:

- Equal pay: HB 179 defined equivalent jobs and work that is equivalent in skill and would have required equal pay for that work, regardless of sex, race and national origin.

- Enforcement: Though not up for debate in 2017, in the 2018 budget session legislators will have the opportunity to improve funding for the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights which investigates discrimination based on sex, race, familial status and more. Between 2008 and 2018, state funding for the Commission has been cut by 19 percent, once inflation is taken into account. Also deeply cut has been the Kentucky Commission on Women.

- Minimum wage: Federal and state inaction on the minimum wage has allowed it to erode to the point that a full-time minimum wage worker cannot keep herself and one dependent out of poverty. HB 178 would have incrementally increased Kentucky’s minimum wage to $15 by 2021 from the current $7.25 an hour. Women make up a disproportionate share of Kentucky’s low-wage workers, meaning that they would also especially benefit from an increase in the minimum wage: 42 percent of all female workers in Kentucky would get a raise from an increase in the federal minimum to $15, compared to 34 percent of men. And though black workers make up 8 percent of Kentucky’s workforce, they comprise 13 percent of the total workforce that would benefit from an increase to $15 an hour, suggesting African American moms would especially benefit.

- Overtime: The federal overtime threshold fails to protect many low-income workers from being required to work more than 40 hours a week without being paid. Clawing back the ground that has been lost over decades of erosion in the rule – with an increase in the threshold to $913 from $455 a week (as proposed in HB 456) – would improve job quality for 25 percent of salaried women compared to 22 percent of salaried men. It would also cover the parents of more than 7 million additional children, nationwide.

Kentucky moms are working hard to support their families and contribute to our economy. Kentucky legislators can and should improve supports and remove barriers to work and economic security for these women and their families.