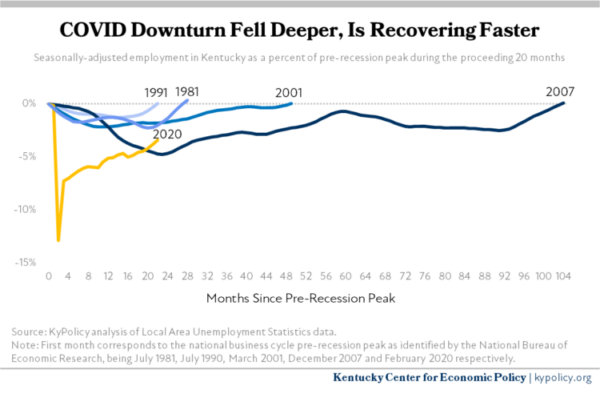

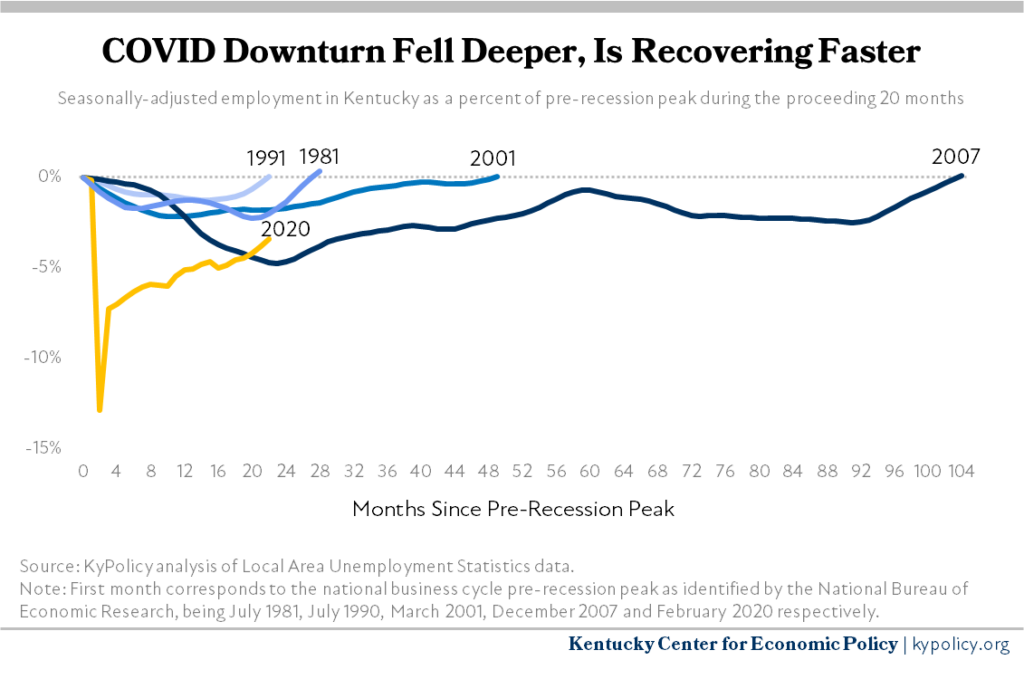

Kentucky is currently experiencing a historically strong recovery from the devastating job losses that occurred as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. By April 2020, Kentucky had lost 294,900 jobs, or employment for roughly 1 in 8 Kentucky workers. This job loss was much deeper than the last four recessions, but job recovery this time has been at a faster pace, as shown in the graph below.

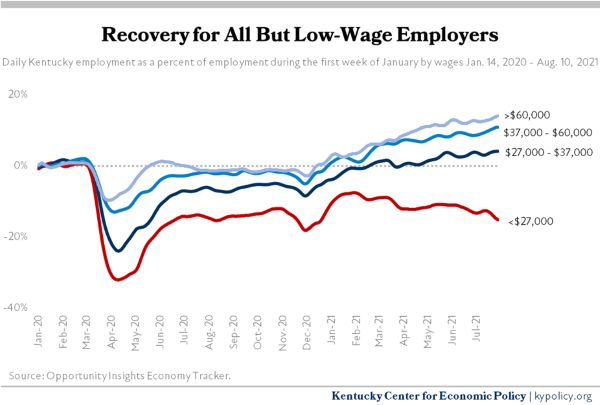

The fact of our strong recovery, and the absence of any significant harm to job growth from multiple rounds of federally boosted unemployment benefits, should put to rest claims that unemployment benefits and other forms of assistance are barriers to getting Kentuckians to work. For businesses offering good and even modest pay, employment has already returned to pre-pandemic levels. Low-wage employers who are struggling to hire people at paltry wages should not be appeased by the General Assembly through cuts to the safety net that increase hardship for Kentuckians.

When looking at the average monthly job growth from the bottom of the downturn through the 19 months since (the latest data available related to the 2020 recession), the recovery from the 2020 recession has outpaced other recent economic downturns by a wide margin. Job growth has averaged 0.22% month-over-month growth, which is nearly 6 times faster than the recovery from 2001, for example.1

Current rhetoric claiming a slow recovery with too few workers is not borne out in the data. What is clear, however, is that employers who offer low wages are struggling to attract applicants. Employment has returned to pre-pandemic levels for employers who offer even modest wages. As the graph below illustrates, the “worker shortage” can be largely characterized as a shortage for employers who continue to advertise positions with low wages. As of last August, jobs paying less than $27,000 per year were still 15% below pre-pandemic levels, while employers offering salaries above $27,000 have fully recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels.

Of course, some Kentuckians remain outside the labor force, and most are in two distinct groups. The first are retirees age 55 and older. From the beginning of 2020, retirements have risen, with 7% more total retirees in the nation in October 2021 compared to January 2020. The majority of those are workers 75 and older, but a substantial number are those age 65-74 as well. Large investment returns resulting in healthier retirement accounts gave many the opportunity to retire with financial security for the first time in years, and so many are taking that opportunity now. Higher risk due to COVID-19 for older people has led some to leave the labor force as well.

The second group are “prime-age” workers between 25 and 54 years old. Nationally, the prime-age employment rate is only slightly lower than pre-pandemic levels, but still over a healthy 80%. Of those not in the labor force, around half are taking care of a family member (like children, an aging parent, a disabled spouse). In fact among prime-age parents, fathers have labor force participation rates close to 95%, whereas mothers of children age 5-17 have labor force participation rates of roughly 75% and mothers of children age 0-4 is under 70%. Child care and family responsibilities are the top two reasons keeping mothers of small children out of the workforce. Other reasons why prime-age workers are outside the labor force are that they either retired early, are attending school, or are sick or disabled, including those who are struggling with Long COVID.

To best help the prime age workers who are currently not in the workforce due to the inability to find and afford child care and elder care, investments should be made to improve the availability and affordability of daycare for their children, expand public preschool, and increase home and community based services for adult loved ones. Employers offering too low pay, little benefits and inadequate workplace flexibility should simply change their practices. Pay is lower than it should otherwise be because of a failure to increase the minimum wage in 13 years along with policies designed to weaken unions.

Instead, the General Assembly is considering policies aimed at making workers more desperate to fill low-wage jobs. House Bill 4, currently in the Senate, cuts unemployment insurance (UI) benefits for people who have lost their jobs — purportedly to encourage those who are not currently in the workforce to begin working again. But there is no evidence that doing so will make any difference in Kentucky’s employment rate, and by definition, cutting UI will make no change to the labor force participation rate as UI claimants are in the labor force. And additionally, even in a hypothetical situation where every Kentucky UI claimant immediately got a job, UI claimants made up less than 1% of the labor force in the last week in January — which is just a fraction of the unfilled positions in Kentucky right now and less than half the average in Kentucky going back to 1987.

Reducing unemployment benefits does not address the underlying issues of low wages and a care sector in tatters – the issues that are the real barriers to remaining prime age workers not reentering the labor force. HB 4 would worsen the quality of life for Kentucky workers and their families, exacerbate existing hardship and reduce economic activity.

- Using the employment peaks and troughs analysis from the National Bureau of Economic Research for the 1981, 1990, 2001, 2007 and 2020 recessions. For the purposes of this analysis, we left out May of 2020, during which 111,839 Kentuckians returned to work, largely through call-backs to previous jobs after COVID-19-related shutdowns ended. If we included May 2020, the average month-over-month jobs growth would be 9,445 and the average monthly jobs growth rate would be 0.53%.