Kentucky has greatly benefitted from the 2010 passage of the federal Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act (ACA). Thanks to the ACA, we were among states with the largest declines in the share of the population without health insurance – gains that also improved equity for Black and Hispanic Kentuckians – and billions of federal dollars have flowed into local economies, creating jobs in clinics and helping keep rural hospitals open. Additionally, nearly 2 million Kentuckians with pre-existing health conditions have protections against harmful insurance company practices that were common before the ACA.

All of that progress is now at risk with California v. Texas, which threatens to repeal some or all of the health reform law and is scheduled for oral arguments in the U.S. Supreme Court in early November. With the possibility of a Supreme Court more hostile to the ACA in place by then, the risks to Kentucky’s health and economy are immense.

Kentucky’s huge coverage gains through the ACA are at stake

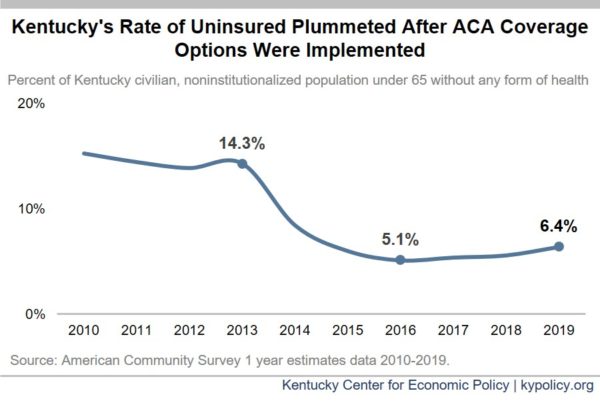

In just four years following the implementation of the ACA’s premium subsidies, protections for people with pre-existing conditions and Medicaid expansion, Kentucky’s uninsured rate fell by nearly two-thirds between 2013 (the year before new coverage options were available) and 2016, down to a historic 5.1% of the noninstitutionalized population. Since that time, the uninsured rate has slowly crept up after state and federal policy changes led to an “unwelcome mat” effect, but the rate remains historically low.

This decline in uninsured rate helped close racial and ethnic disparities in coverage rates in Kentucky. Between 2013 and 2019, the uninsured rate for white Kentuckians fell from 13.6% to 6.0%, for Black Kentuckians it fell from 17.5% to 7.4%, and for Hispanic/Latino Kentuckians it fell from 32.3% to 20.0%.

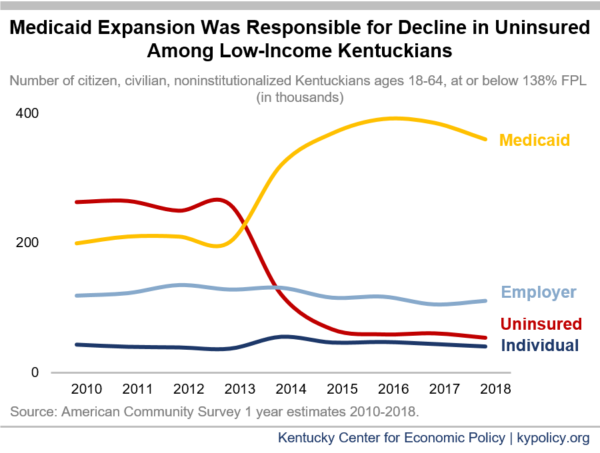

The main drivers of the decline in uninsured Kentuckians were the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to all adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL – equal to a 1-person household with roughly $17,600 in annual income) and premium subsidies for the individual coverage marketplace (what our state called kynect). Although over 80,000 Kentuckians were able to get coverage through the marketplace – 4 in 5 of whom received financial assistance – many more gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion. According to annual data from the Census Bureau, between 2013 and 2018 there were 206,000 fewer uninsured Kentuckians with incomes at or below 138% of FPL; and among the same population, 157,600 more were enrolled in Medicaid (the total number of Kentucky adults under 138% FPL fell 11.8% during this time, partially explaining why Medicaid numbers went down between 2016 and 2018). As of August 2020, there were nearly 480,000 Kentuckians enrolled in health coverage through the Medicaid expansion (according to enrollment data provided by the Department for Medicaid Services); enrollment in Medicaid expansion has grown by nearly 40,000 since February due to the COVID-19 economic downturn.

Combined, over 562,000 Kentuckians are enrolled in marketplace plans or Medicaid expansion. This does not include people ages 18-26 who, because of the ACA, are now allowed to stay on their parents’ health plans. Nor does it include others who have received coverage through small business plans that are also sold on the marketplace. Strong coverage gains are consistent across the state, but most concentrated in eastern Kentucky as shown below.

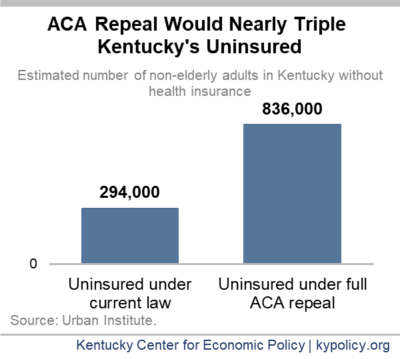

If the Supreme Court strikes down coverage options in the ACA, most of the 1 in 8 Kentuckians currently covered by the ACA would go without insurance. According to an estimate from the Urban Institute, Kentucky’s number of uninsured would spike 184.4% from 294,000 to 836,000, bringing our uninsured rate up to 22% – far higher than it was in 2010 before the ACA. This would be the third largest percent in the number of uninsured among states.

In the midst of a global pandemic that has disproportionately affected Black people, an overturn of the ACA would lead to a 211% increase in the uninsured rate for Black Kentuckians, according to the Urban Institute. An end to ACA coverage options would also triple the uninsured rate among white Kentuckians, and would increase the uninsured rate 48% for Hispanic Kentuckians.

The same set of estimates show that young Kentucky adults (age 19-26) would have the largest increase in the uninsured rate at 270%. The other age categories (up to 64) all have increases in the uninsured rate by at least 156%, including children.

Nearly two million Kentuckians with pre-existing conditions could be charged more for or denied health coverage

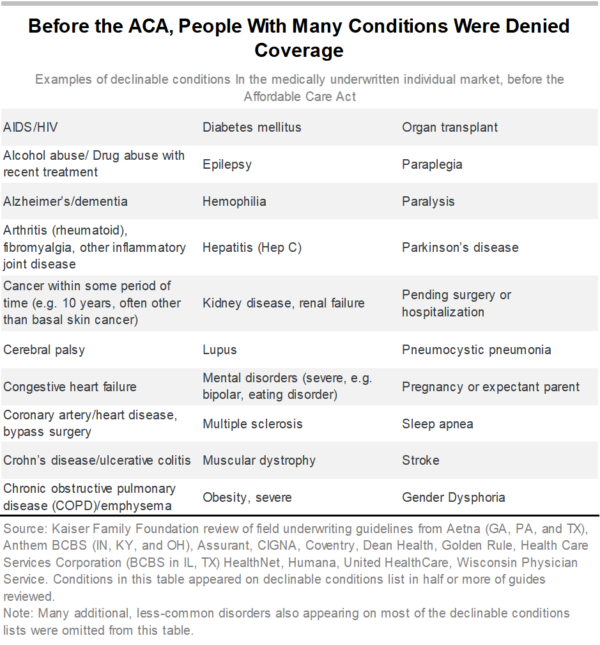

Nearly 1.8 million non-elderly Kentuckians have a pre-existing health condition that, were it not for specific protections in the ACA, could lead to serious barriers to health insurance like higher premiums, denied medical services or more cost-sharing. Of those, approximately 890,000 are estimated to have conditions so severe that an insurance company could deny them coverage altogether.

Pre-existing conditions include a broad array of illnesses and chronic conditions, but also include past conditions from which people have recovered. They even include the potential of someone to need health coverage in the future – such as being a woman of child-bearing age. Further, there are now 80,000 Kentuckians who have survived COVID-19, which could be considered a pre-existing condition that insurers could discriminate against without ACA protections. Prior to the ACA, people in these groups were underinsured or uninsured altogether if they did not get health insurance at work or through Medicaid and their only coverage option was purchasing insurance directly from an insurance company, often called “individual insurance.”

Besides turning people down for coverage, prior to the ACA insurance companies increased premiums above their normal rates, excluded certain kinds of treatment for specific health conditions, increased deductibles or excluded certain benefits altogether (such as prescription drug coverage) for people with pre-existing conditions. Some insurance companies also practiced what is known as “rescission,” which is when coverage is revoked after an individual develops a condition the insurer decides is too expensive to cover – leaving a sick person without coverage when they need it the most.

Other critical protections in the ACA are also at stake

In addition to protections for people with pre-existing conditions, the ACA provides consumer protections aimed at improving health and reducing financial hardship. These protections, at stake in the lawsuit, included:

- A requirement that insurers provide a set of “essential health benefits.” These include services like maternity care, prescription drugs, mental health care and preventive screenings. Prior to this requirement, very few health plans offered all of the essential health benefits and those that did were often expensive.

- Bans on insurance companies placing annual and lifetime caps on the amount of medical care a patient could receive. Prior to the ACA, an insurer could drop a patient from an insurance plan mid-year for requiring too much care.

- Reined-in out-of-pocket costs for patients. Whereas before there was no limit on how much an insurance company could require in out-of-pocket costs, now an individual is capped at around $7,000 per year.

The ACA has boosted Kentucky’s economy, repeal would lead to widespread layoffs

The ACA health care programs not only provide hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians the opportunity to get medical care when they need it, but they also are a powerful stimulus that sustains thousands of jobs and boosts local economies. In 2020, $407.8 million in federal dollars will be spent in Kentucky through the insurance subsidies on the exchange, and in 2019, $2.8 billion in federal funds helped pay for our Medicaid expansion (it will almost certainly be more this year as COVID-19-related layoffs have led to a large increase in Medicaid enrollment). Combined, subsidized marketplace coverage and Medicaid expansion invest over $3 billion into Kentucky’s economy every year.

This funding helps to pay health care professionals like doctors, physicians assistants, nurses and others, as well as auxiliary staff like janitors and administrative assistants. The two main sectors that make up the bulk of health care jobs supported by ACA coverage – hospitals and ambulatory health care services – paid better than other industries on average in 2018 – $5,106 compared to $4,284 per month.

Other sectors also benefit from increased federal investment through the ACA. This happens both as the health industry does business with other industries such as construction and finance, and as health care workers spend their salaries in other sectors like retail and food – all of which supports jobs and spending across the economy. Repeal of the ACA would have a devastating economic effect In 2017, when Congress was considering a repeal of the ACA, the Commonwealth Fund estimated that 44,500 Kentuckians would lose their jobs in a range of sectors, including:

- 17,100 in health care,

- 4,600 in construction and real estate,

- 6,000 in retail trade,

- 2,000 in finance and insurance,

- 1,400 in public employment,

- And 13,500 in other private industries.

Improved financial viability of the health care sector through ACA coverage options has also helped preserve health care capacity, especially for people in rural communities where hospitals and other facilities face greater risk of closure. One study of 1,395 rural hospitals found that in the first year of the expansion, rural hospitals in expansion states remained in the black, with operating margins of 1.03%, whereas rural hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid eligibility had operating margins in the red, at -0.18% – a result that has been confirmed in recent years. According to a UNC tracker of rural hospital closures, 73% of rural hospital closures since 2014 happened in a state that had not expanded Medicaid eligibility at the time of its closure. This includes 12 hospital closures in Tennessee.

Repeal would sacrifice health to give tax cuts to the wealthy

If the ACA is struck down entirely and Medicaid expansion and subsidies on the health insurance exchange end (as well as the exchange itself), there will be a catastrophic loss of coverage. And at the same time the commonwealth would lose critical access to health care and jobs across many sectors – likely while we’re still fighting a global pandemic and historic recession – a small number of wealthy Kentuckians would get a windfall in their tax bills. According to the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy, if the ACA is repealed, Kentuckians earning between $200,000-500,000 would see a tax benefit of $530 on average, and those earning between $500,000 and $1 million would see an average tax benefit of $3,870. But for those earning over $1 million, the average tax benefit would be $68,780 per year. Forsaking the health of Black, brown and white low- to moderate-income Kentuckians, people with pre-existing conditions and vital sectors of our economy in exchange for tax breaks for the wealthy few would leave everyone worse off in the end.

While the lawsuit was making its way through the lower courts, the Trump administration switched from defending the law, to arguing for its demise. The Justice Department should return to defending the law in court, along with the 17 states including Kentucky (represented by Governor Beshear) that have stepped up to defend the ACA. With Amy Coney Barrett likely to be added to the Supreme Court, the fate of California v. Texas is largely unknown, especially in light of her past criticism of the ACA and Supreme Court decisions related to it. The well-being, employment and lives of Kentuckians are on the line in the decision.

Updated October 23, 2020.