Workers at the Ford/BlueOval SK (BOSK) battery plant in Glendale, Kentucky have filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board to unionize and join the United Auto Workers (UAW). 1 This campaign to improve wages and working conditions comes on the heels of the UAW’s hugely successful 2023 contract with the Big Three U.S. automakers, which directly benefitted Kentucky workers at unionized Ford and GM facilities in Louisville and Bowling Green and their communities. The announcement of BOSK’s unionization effort and UAW’s historic victory come at an important time for Kentucky’s autoworkers. While the industry has become central to Kentucky’s economy in recent decades, and has benefitted from large public subsidies, auto worker job quality has also been on the decline.

Read this report as a PDF.

A victory by BOSK workers would result in significant job improvements and could help pave the way for better jobs across Kentucky’s auto industry and even beyond. Because of the prominent and pervasive role of the auto industry in the state, increased unionization could create ripple effects in other workplaces. It is exactly the kind of worker-led action needed to put Kentucky’s economy on the high road of good quality jobs that allow families to thrive. In doing so, it could be an important step toward ending decades of wage stagnation and catalyzing a stronger economy for all Kentuckians.

Kentucky’s auto industry has grown and is a significant part of the Kentucky economy

For nearly 70 years, the auto industry has been an important part of the Kentucky economic landscape. Louisville became a site in the Ford production fleet when the Ford Assembly Plant was established there in 1955, and that city’s role expanded with the Kentucky Truck Plant opening in 1969. The state added a General Motors facility when the Corvette plant began operation in Bowling Green in 1980. And the trend greatly accelerated when Toyota announced it would build its first North American facility and its largest plant in the world in Georgetown in 1985, part of a broad migration of the auto industry throughout the U. S. South, and a trend that continues today in the transition to electric vehicles.

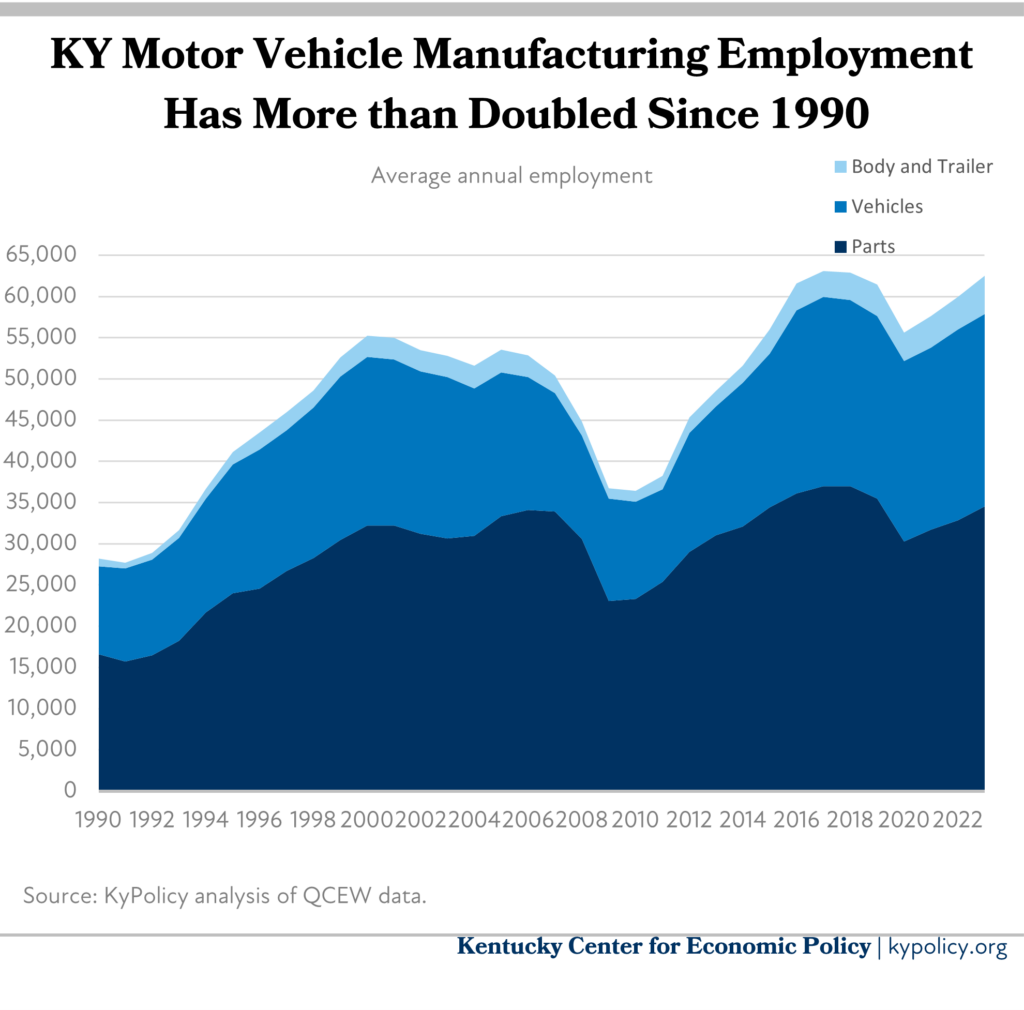

The number of Kentucky jobs in automobile manufacturing grew by 136% from 28,000 in 1990 to 66,000 in 2023. This growth far outpaces Kentucky employment more broadly, which grew 38% during that same timeframe. Decisions to outsource and offshore production coupled with the Great Recession and short-sighted management decisions in the American auto industry harmed employment in the sector, which fell from 53,000 jobs in 2006 to 36,000 by 2010.2

But the industry has slowly been recovering since, and employment is now near a record high. The biggest subsectors are in auto parts manufacturing, which employs 35,000 workers, and auto assembly, which employs 23,000.

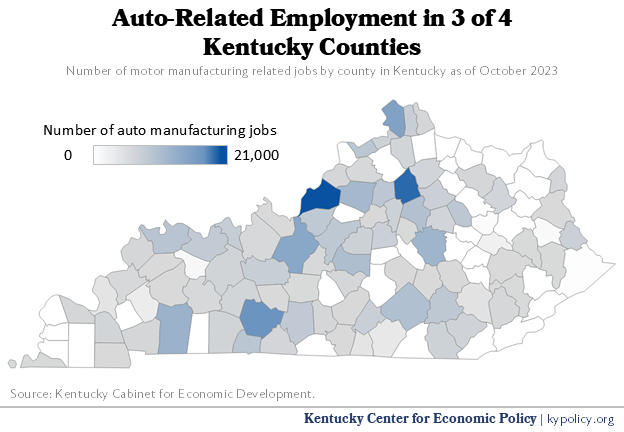

In fact, Kentucky is among the states where the auto industry is most significant to the local economy. Kentucky is first among all states in its location quotient of motor vehicle manufacturing — which measures the concentration of specific industries in a given area compared to the rest of the country — third for motor vehicle parts manufacturing, and fourth for motor vehicle body and trailer manufacturing.3 The Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, using a broader definition of the industry, says the state has over 550 automotive-related facilities that employ 105,292 people, and is the nation’s “#1 producer of cars, light trucks and SUVs per capita.”4 Those facilities are distributed across 87 counties, as shown in the map below.

Autos have also become more important within Kentucky’s manufacturing sector. Total manufacturing employment in Kentucky rose from 260,000 jobs in 1990 to a peak of 307,000 by 2000 before declining in the following decade due in part to trade agreements like NAFTA and the decision to admit China into the World Trade Organization.5 The Great Recession then took its toll, and despite an uptick in the last few years manufacturing has fallen from 19% of total Kentucky employment in 1990 to 13% in 2023. However, the share of the state’s manufacturing jobs that are in the auto industry has increased, rising from 11% of total manufacturing employment in 1990 to 25% in 2023.6

The transition toward electric vehicles (EV) has resulted in new investments. Spurred in large part by federal policies like the Inflation Reduction Act, companies are investing in new and retrofitted facilities for EV production, component and battery manufacturing, and battery recycling. Kentucky is one of the 10 states that together have received 84% of the announced new EV investments, which in Kentucky total approximately $13.1 billion and are expected to result in 13,800 jobs.7 That includes the $5.8 billion BOSK battery plants in Glendale expected to bring 5,000 jobs, the $2 billion AESC plant in Bowling Green with 2,000 jobs, a $1 billion Ascend Elements facility in Hopkinsville that will provide 460 jobs in battery recycling and materials, and $1.8 billion at Toyota in Georgetown to transition production for EVs.

Auto worker job quality has slowly eroded, and is inadequate

Auto industry jobs have long been perceived as relatively good and high-paying. But they became good jobs in the 20th century only because a critical mass of workers in the industry unionized, and job quality has declined as union density has fallen. Within Kentucky, these jobs are important to the state economy, especially for workers who may lack a college degree, but their quality has fallen even as the industry has boomed.

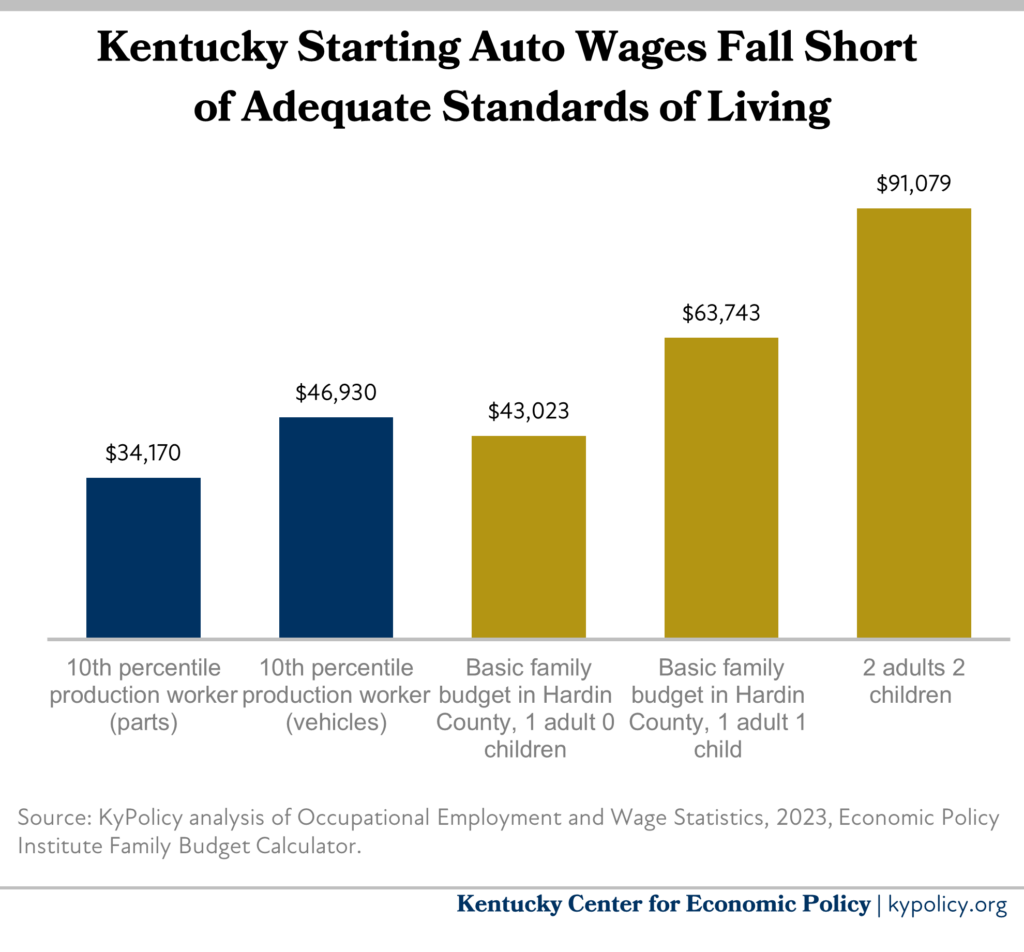

In 2023, an entry-level Kentucky auto worker whose earnings were at the 10th percentile made only $34,170 per-year in parts manufacturing and $46,930 in assembly.8 For all 144,110 manufacturing production occupations in Kentucky, the 10th percentile wage was $32,800. That puts auto assembly jobs above typical manufacturing employment in wages, in large part because of the unionization of the Kentucky Ford and GM plants and the pressure that puts on non-union employers like Toyota. But the wages for auto parts jobs, which are largely non-union, are barely better than typical manufacturing employment.

These wages also fall far short of the rising cost of living, especially for workers with children. A family of two adults and two kids needs an estimated $91,079 to meet a basic family budget in Hardin County, the location of the BOSK plants, and a state-wide housing shortage is driving costs higher.9 A family of one adult and one child needs $63,743. Even more experienced workers would struggle under the pay that is currently available in the industry.

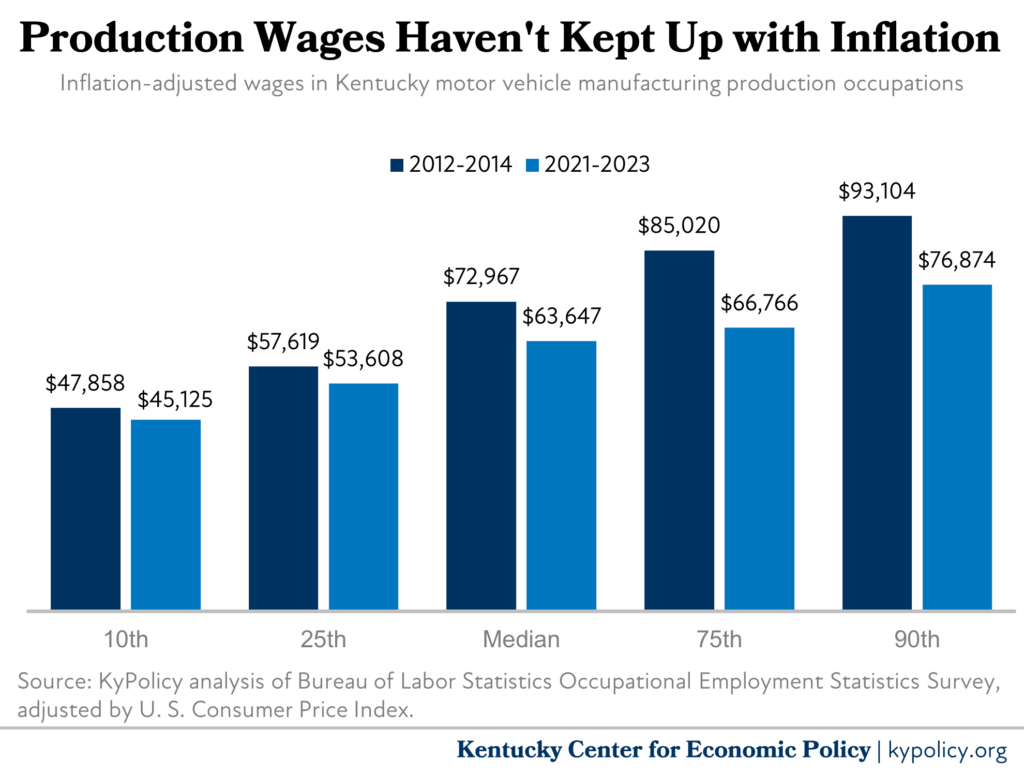

These wages have not kept pace over time. Total wages per employee are down by one-third in inflation-adjusted dollars from what they were in 2007 before the Great Recession.10 Compared to 2012-2014, the median annual wage in automobile production is down 13% after taking inflation into account, equivalent to a $4.48-an-hour pay cut, or a loss of $9,321 annually.11

Auto manufacturing, auto parts and body and trailer manufacturing were 3.2% of all jobs in the state in 2023, approximately the same share as in 2000 except for a dip after the Great Recession. But as a share of total wages paid in the state, the industry has fallen from 5.2% in 2000 to just 4% today.12 That means wages remain above average, but the premium paid for auto jobs compared to other Kentucky jobs is narrowing.

This trend is not unique to Kentucky but has been mirrored across the south and the auto industry in general.13 The industry has intentionally moved south in part to pay lower wages and undermine job quality in their traditional locations in the Midwest. Average U. S. auto assembly wages have fallen 19.3% since 2008 after adjusting for inflation, and auto parts wages have fallen 10%.14

Despite enormous public subsidies of the industry and strong profits, job quality has been stuck in a lower gear

The growth of the auto industry in Kentucky was made possible in part by a huge amount of public subsidies including in the form of tax incentives, cash subsidies, training funds, land and industrial site development, water and road infrastructure improvements, and more. States have increased their use of tax breaks and other subsidies in recent decades as they compete for industries.

In some ways, Kentucky launched the subsidy “war between the states” in 1985 when it provided a landmark $147 million in a variety of incentives to help attract Toyota’s first North American plant to Georgetown (a package that would equal an enormous $429 million in today’s dollars). Over a period of 50 years, Kentucky has provided subsidies totaling $664 million to Toyota and its various subsidiaries, according to Good Jobs First.15 The most recent package was $240 million awarded in 2023, which will be paid out through 2032. Kentucky’s tax breaks to Toyota and other companies include exemptions from paying the corporate income tax as well the awarding of job assessment fees, in which all or a portion of employees’ individual income taxes are diverted to the company rather than being paid to the state. Kentucky was the first state to provide this form of subsidy in the 1990s.

The new BOSK battery plants are also heavily subsidized with public tax dollars. In a 2021 special session, the General Assembly awarded what became $250 million in upfront cash to the facility in the form of a forgivable loan, $27 million in land in Hardin County, and $25 million in state-funded training.16 In addition, the U. S. Department of Energy has awarded $9.2 billion in conditional loans to BOSK for its battery plants in Kentucky and Tennessee.17 The future viability of EVs also depends in part on other aspects of the Inflation Reduction Act remaining in place under the new Congress and Trump administration, including the $7,500 tax credit for the consumer purchase of EVs.18

With so much public money used to subsidize the auto industry, it is a reasonable expectation that the jobs the sector produces should set the standard for quality. And the rising profits of these companies certainly make it possible for them to afford higher wages. Ford’s profits are $3.7 billion over the most recent year, while Toyota’s are $37 billion, making it the most profitable car company in the world.19 Ford’s CEO makes $26 million in compensation, up 26% from the prior year, while Toyota’s CEO makes $10 million, an increase of 62% from the previous year.20

UAW contract is turning job quality problem around

The pressure from successful UAW bargaining is beginning to turn the auto job quality problem around. Following a six-week strike, the UAW won major contract victories in 2023 that apply to the unionized Kentucky Truck Plant and Ford Assembly Plant in Louisville as well as the General Motors Corvette facility in Bowling Green. That included a 25% increase in wages for Ford UAW workers, among other improvements.21

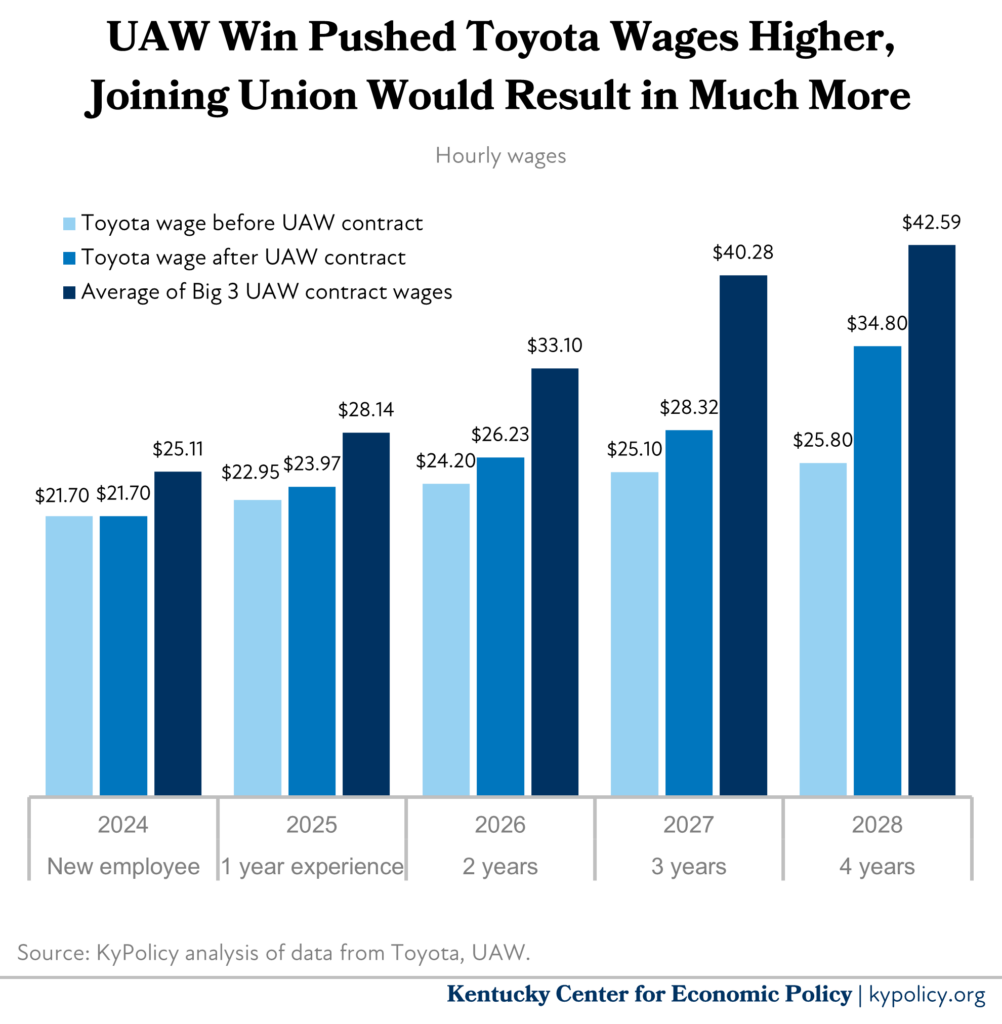

The pressure from higher wages at those unionized auto facilities resulted in quick action at non-union Kentucky plants to boost wages. In December, after the UAW announced their BOSK union drive publicly, BOSK announced starting wage increases from $2.50- to $3.50-an-hour.22 In addition, the Toyota facility in Georgetown immediately announced wage increases after the new UAW contract that would result in a worker making $34.80 after four years instead of the previous wage of $25.80.

However, significantly more can be gained from these non-union facilities joining the UAW. For example, the UAW contract starting wage is an average of $25.11 (and $26.32 at Ford) compared to $21–an-hour at both BOSK and Toyota. And the wage in 2028 for an employee with four years’ experience is $42.59-an-hour on average at the Big Three plants (Ford, GM and Stellantis) compared to $34.80 at Toyota, or 22% higher.

More can be gained through unionization of non-union facilities

Unionization has a positive economic impact beyond the workers who will receive higher wages and better working conditions. The auto industry’s central role in the Kentucky economy makes it a standard-setting industry for wages and job quality in the state. When its employers increase pay, other similar employers must also increase wages to compete for workers, as demonstrated in the example of Toyota above.

Also, there are ripple effects for the economy from the spending that results from higher wages. According to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, the economic activity from higher union wages at Toyota in Kentucky would lead to an additional $82 million in state economic output per year, resulting in $5 million more in state, county and local tax revenues and 470 more jobs, 78% of which will not require a four-year college degree.23 More money in Kentucky workers’ pockets means more spent at local businesses, helping the broader community.

The auto industry has become very important to Kentucky’s economy, and the transition to electric vehicles is increasing its significance. The industry has also been heavily subsidized with public tax dollars over the history of its growth in the commonwealth, and profits are very high. At the same time, job quality has declined in the industry in recent decades, reducing the livelihoods of auto workers and limiting the resulting positive economic impacts. But the UAW’s contract win in 2023 sets a new standard that can put job quality on a new and promising trajectory. Further unionization of the industry, starting with the BOSK battery plants, would reap positive benefits for workers, their communities and the state as a whole.

Photo: UAW

- United Auto Workers, “Supermajority of Workers at EV Battery Maker BlueOval SK in Kentucky Have Signed Union Cards, Launch Public Campaign to Join UAW,” Nov. 20, 2024, https://uaw-newsroom.prgloo.com/press-release/supermajority-of-workers-at-ev-battery-maker-blueoval-sk-in-kentucky-have-signed-union-cards-launch-public-campaign-to-join-uaw. Luis Feliz Leon, “Kentucky Battery Workers Launch Union Drive with UAW,” Labor Notes, November 21, 2024, https://www.labornotes.org/2024/11/kentucky-battery-plant-workers-launch-union-drive-uaw.

- Adam S. Hersh, “UAW-Autoworkers Negotiations Pit Falling Wages Against Skyrocketing CEO Pay,” Economic Policy Institute, September 12, 2023, https://www.epi.org/blog/uaw-automakers-negotiations/.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, 2023 annual averages.

- Cabinet for Economic Development, “Kentucky: Leading the Way Toward an Electric Future,” October 2023, https://ced.ky.gov/LP/electric_vehicle. https://cedky.com/cdn/kyedc/Motor%20Vehicle%20Related%20Facilities%20in%20Kentucky_Oct2023.pdf.

- KyPolicy analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data. Robert E. Scott and Zane Mokhiber, “Growing China Trade Deficit Cost 3.7 million American Jobs Between 2001 and 2018,” Economic Policy Institute, Jan. 30, 2020, https://www.epi.org/publication/growing-china-trade-deficits-costs-us-jobs/.

Robert E. Scott, “Heading South: U. S.-Mexico Trade and Job Displacement After NAFTA,” Economic Policy Institute, May 3, 2011, https://www.epi.org/publication/heading_south_u-s-mexico_trade_and_job_displacement_after_nafta1/. - KyPolicy analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data.

- Environmental Defense Fund, “U. S. Electric Vehicle Manufacturing Investments and Jobs,” August 2024, https://www.edf.org/media/us-electric-vehicle-manufacturing-investments-jobs-continue-grow.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics Survey data.

- John Cheves, “Kentucky is 200,000 Homes Short of What It Needs and the Gap Is Widening. Now What?” Lexington Herald-Leader, Nov. 20, 2024, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article295428394.html.

- KyPolicy analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data.

- May 2023 OEWS Research Estimates.

- KyPolicy analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data.

- Chandra Childers, “Southern Economic Policies Undermine Job Quality for Auto Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, September 4, 2024, https://www.epi.org/publication/rooted-racism-auto-workers/.

- Hersh, “UAW-Autoworkers Negotiations.”

- Good Jobs First Subsidy Tracker, accessed Nov, 22, 2024, https://subsidytracker.goodjobsfirst.org/?company_op=starts&company=Toyota&state=KY&order=sub_year&sort=asc.

- Chris Otts, “Kentucky’s EV Battery Deals Carry Big Costs for Taxpayers,” WDRB, Dec. 8, 2022, https://www.wdrb.com/in-depth/kentuckys-ev-battery-deals-carry-big-costs-for-taxpayers/article_fc02d752-7743-11ed-bd2a-5348490dfdee.html. HB 5 of the 2021 Special Session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21ss/sb5.html.

- U. S. Department of Energy, “LPO Announces Conditional Commitment for Loan to BlueOval SK to Further Expand U.S. EV Battery Manufacturing Capacity,” June 22, 2023, https://www.energy.gov/lpo/articles/lpo-announces-conditional-commitment-loan-blueoval-sk-further-expand-us-ev-battery. Reuters, “US Finalizes $9.63 Billion Loan for Ford, SK On Joint Battery Venture,” Dec. 16, 2024, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/money/2024/12/16/blue-oval-sk-loan-gets-9-63-billion-loan/77020486007/.

- Austin Horn, “What Would a Trump Presidency Mean for Kentucky’s Growing Electric Vehicle Industry?” Lexington Herald-Leader, Nov. 1, 2024, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article294842759.html.

Austyn Gaffney, “The Clean Energy Boom in Republican Districts,” The New York Times, Nov. 21, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/21/climate/ira-republicans-clean-energy.html. - Macrotrends, Ford Motor Operating Income 2010-2024, https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/F/ford-motor/operating-income. Macrotrends, Toyota Operating Income 2010-2024, https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/TM/toyota/operating-income.

- Phoebe Wall Howard, “Ford Salaries in 2023: How Much CEO Jim Farley Earned,” Detroit Free Press, March 29, 2024, https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/ford/2024/03/29/ford-salaries-2023-how-much-ceo-jim-farley-earned/73142747007/. Nicholas Takahashi, “Toyota Chair Pay Raised to $10 Million Despite Safety Probe,” Bloomberg, June 25, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-06-25/toyota-chair-pay-raised-to-10-million-despite-safety-probe.

- https://uaw.org/ford2023/.

- Olivia Evans, “Ford, SK On Electric Vehicle Battery Park in Glendale to Raise Wages. Here’s What We Know,” Louisville Courier-Journal, Dec. 17, 2024, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/money/companies/2024/12/17/blueoval-sk-to-raise-wages-at-kentucky-ev-battery-park/77049994007/.

- Economic Policy Institute IMPLAN analysis.