Stagnant or falling real wages for many Kentucky workers threatens their standard of living and is leading to growing income inequality. One of the causes of inadequate wages is the failure of state and federal governments to adjust the minimum wage to keep up with inflation. That neglect includes the minimum wage for tipped workers, which has not been increased in 23 years.

House Bill 191 in the 2014 Kentucky General Assembly would gradually raise the minimum wage for tipped workers from $2.13 an hour to 70 percent of the regular minimum wage. It is a necessary companion bill to House Bill 1, which raises the minimum wage for non-tipped workers to $10.10 an hour over three years. Together, the two bills update the minimum wage in ways similar to the Fair Minimum Wage Act introduced in Congress.

Here are the reasons why raising the tipped minimum wage makes sense:

Tipped workers are a growing portion of the workforce, and many of them don’t make enough in wages to avoid poverty

The sectors that employ tipped workers have been growing in recent years. Employment in the industry “food services and drinking places” has increased 15.1 percent since 2003 while total employment has increased only 2.3 percent over that time.1 That mirrors national trends, where the growth in tipped employment far exceeds job growth in general over the last decade. So while the economy has shed jobs in manufacturing, construction and other sectors, the workforce is increasingly made up of service sector jobs, including jobs that rely on tips.

Nationally, 61 percent of tipped workers are waiters; 15 percent are hairdressers and hairstylists, and 11 percent are bartenders. The tipped workforce is disproportionately female—73 percent of tipped workers are women. And tipped workers are overwhelmingly adults. 88 percent are at least 20 years old and nearly half are at least 30. Among waiters, 82 percent are 20 or older.

Kentucky is one of 13 states in which the tipped minimum wage is still only $2.13 an hour, where it has remained since 1991. Tips are supposed to increase workers’ total wages to more acceptable levels, but the reality is that many tipped workers don’t make enough to avoid poverty.

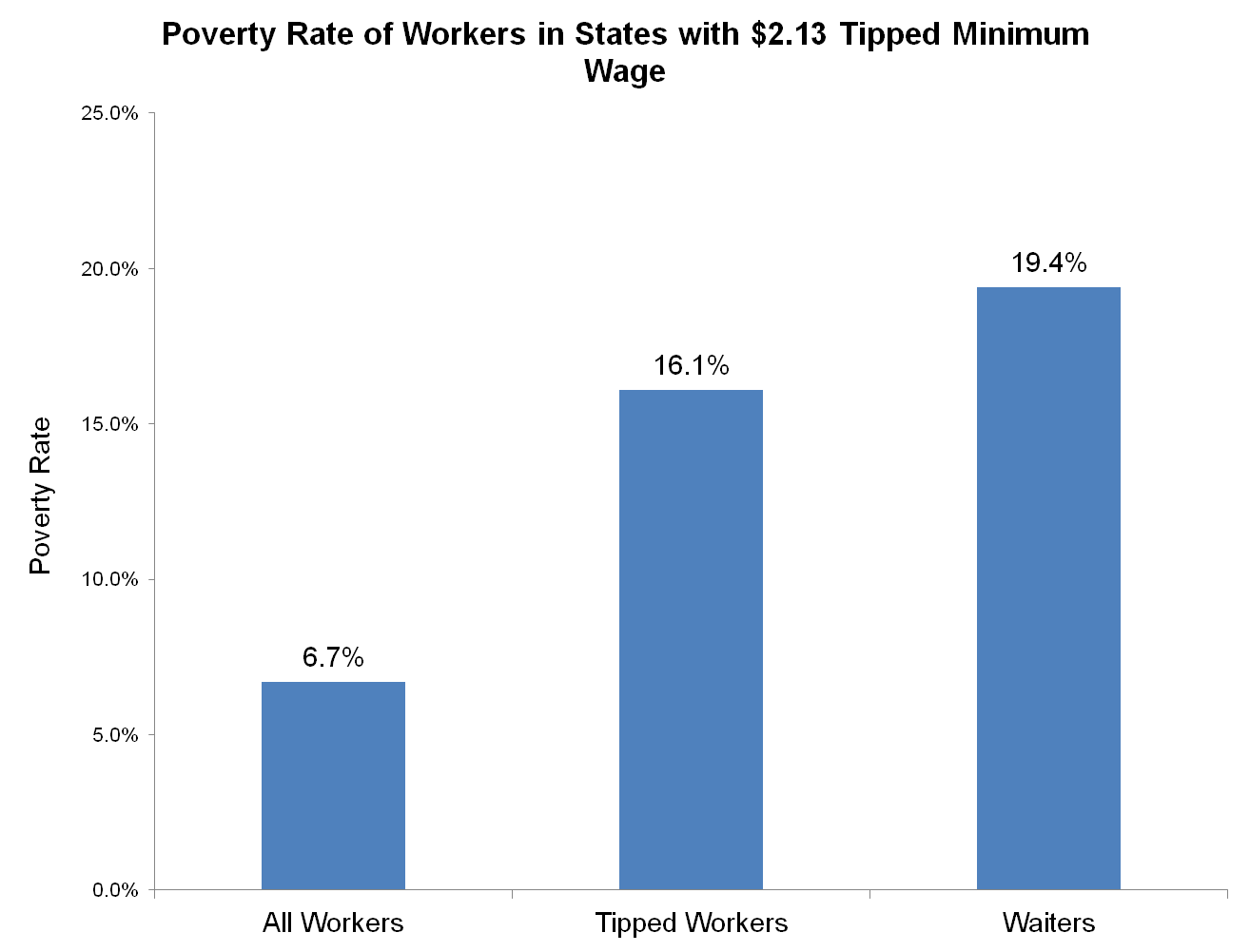

In those states that have a $2.13 minimum like Kentucky, the poverty rate is more than twice as high for tipped workers as it is for all workers, and the poverty rate is nearly three times higher for waiters and waitresses. 16.1 percent of tipped workers in states with a low tipped minimum wage like Kentucky live in poverty and 19.4 percent of waiters live in poverty, compared to only 6.7 percent of all workers.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

Other challenges with tipped work exacerbate the low wages. Income from tips is volatile and subject to a variety of factors like shift assignments, season of the year and the economy. Odd hours can make child care difficult to find and expensive. And these jobs are often physically demanding. Constant contact with customers subjects workers to illness that can mean lost work time.

It should also be noted that many tipped workers don’t receive benefits. 71% of private sector workers have access to some type of healthcare benefits compared to just 37% of workers in food services. Retirement benefits are provided for 65% of private sector workers but just 32% of workers in food services.

Decline in the real value of the tipped minimum wage is a big cause of the higher rates of poverty endured by many tipped workers

From 1966 to 1996 the tipped minimum wage was at least 50 percent of the federal minimum wage. When the federal minimum wage was increased in 1996, that link was broken. The relative value of the tipped minimum wage has since declined to only 30 percent of the regular minimum wage.

Because the regular minimum wage itself has lost 30 percent of its real value since the 1960s, the tipped minimum wage has lost 60 percent of its value over that time.

Raising the tipped minimum wage makes a difference for workers’ well-being. The poverty rates for tipped workers in states like Kentucky with a tipped minimum wage of only $2.13 is 16.1 percent compared to 12.1 percent in states where tipped workers receive the full minimum wage. The median wage for waiters in states with a $2.13 tipped minimum is only $8.77, while it is $10.27 in states where the minimum wage is the same for tipped and non-tipped workers.

Raising the tipped minimum wage won’t decrease employment

Contrary to the claim that raising the minimum wage decreases employment, tipped workers make up a consistent share of the workforce across the country, from states where the minimum is just $2.13 per hour to states where they are paid the full minimum wage. In other words, states that have raised the minimum wage for tipped workers do not have a smaller tipped workforce.

The impact of the minimum wage on employment is one of the most studied questions in economics, and the overwhelming conclusion is that modest increases have little to no impact on employment. That’s because businesses have multiple channels of adjustment to use besides shedding jobs in response to a higher minimum wage. Higher wages can be absorbed through reduced worker turnover and training costs, compressed wages at the top, improvements in organizational efficiency and a variety of other means.

All of these reasons to raise the tipped minimum wage are why many states have already taken action. In 2011, only 31 percent of the workforce was still in a state with a $2.13 minimum for tipped workers. As mentioned previously, only 13 states still set the tipped minimum at $2.13. 24 states have a tipped minimum that is higher including West Virginia, Ohio and Missouri, and in 7 states the tipped minimum is the same as the non-tipped minimum wage.