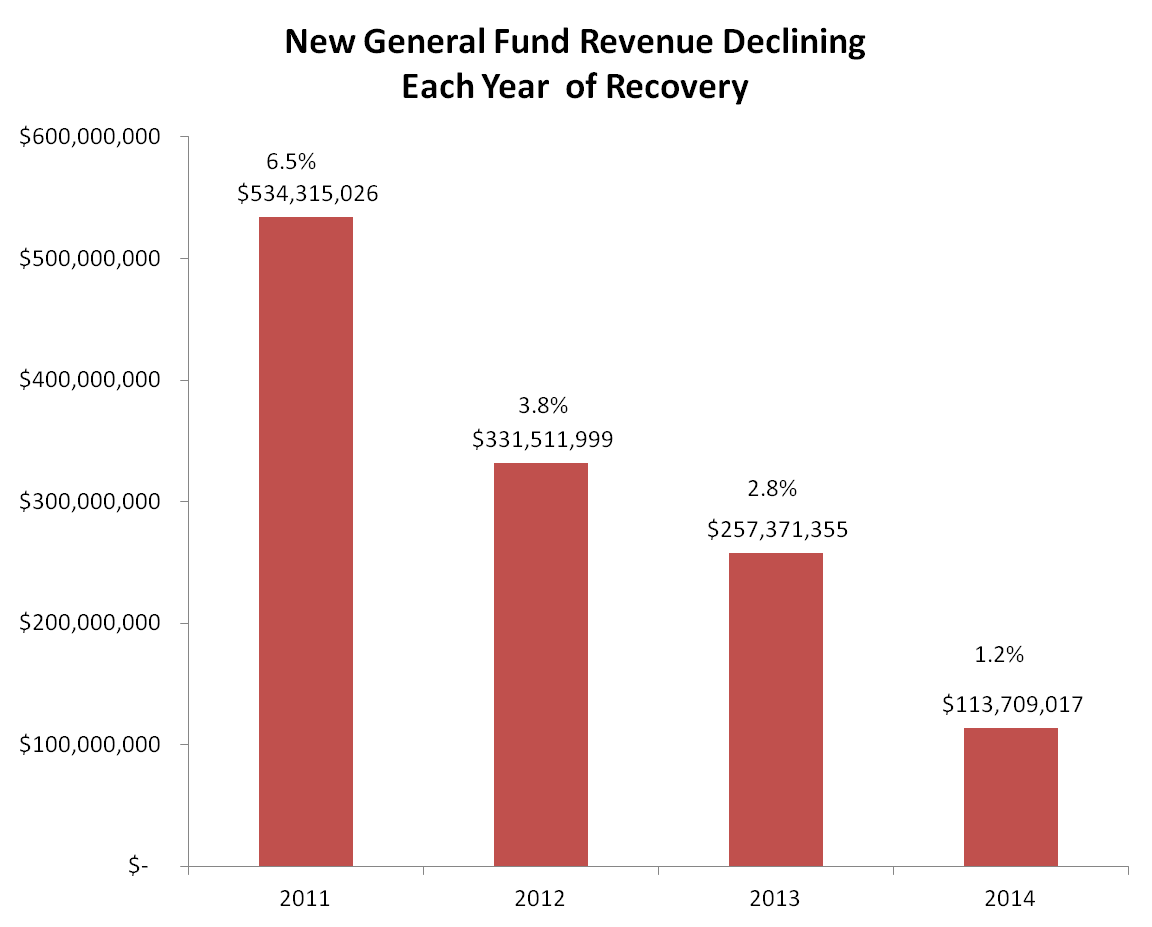

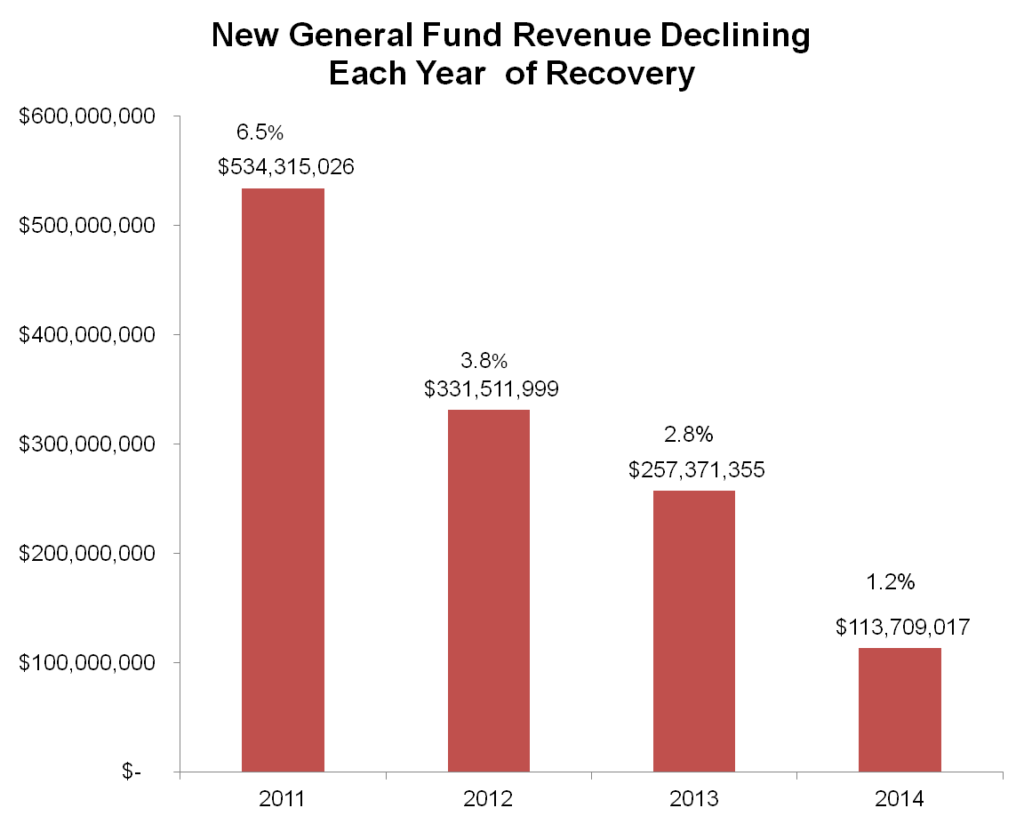

The rate of revenue growth in Kentucky’s General Fund has slowed down between 2011 and 2014, as seen in the graph below. That’s a big part of why Kentucky’s budget has been so tight even this far into the economic recovery.

Source: KCEP analysis of Office of the State Budget Director data.

Source: KCEP analysis of Office of the State Budget Director data.

Here are five big reasons for this falling rate of growth:

Income taxes grew quickly at the beginning of the recovery.

Revenue from individual and corporate income taxes grew rapidly the first few years of the recovery. In part, that was because a bounce-back in the financial markets and income growth for those at the top translated into tax revenues. The individual income tax grew by $263 million or 8 percent in 2011, making up nearly half of all state revenue gains that year. Since then, individual income tax growth has been more modest, and a one-time capital gains tax issue shifted some income tax revenue from 2014 to 2013. Revenue from corporate income taxes and the limited liability entity tax (an alternative corporate income tax) has also grown rapidly in the recovery due to high corporate profits, but growth is beginning to taper off. Revenue grew 35 percent in 2011, 11 percent in 2012, 12 percent in 2013 and only 4 percent in 2014.

Sales taxes have been weak due to too few jobs and stagnant wages.

Since the sales tax is a regressive tax paid disproportionately by low- and middle-income Kentuckians, it depends heavily on their ability to spend. That’s been limited by continued high unemployment and weak wage growth for those who have jobs. Sales tax revenue has actually declined in three of the last six years. Growth was stronger in 2012, at 5.4 percent, in part because of one-time spending due to pent-up demand from the recession according to the Office of the State Budget Director. Limited taxation of services also impedes sales tax growth.

Tax amnesty inflated revenues in 2013.

To help balance the budget during weak revenue growth, the state put in place a tax amnesty program in 2013 that netted a total of $58.4 million for the General Fund. Tax amnesty allows those who owe back taxes to pay them without a penalty, meaning a one-time infusion of funds.

Coal severance tax revenues were strong in 2011 and 2012, but have since collapsed.

Coal severance tax revenues were strong early in the recovery due to high prices for eastern Kentucky coal and growth in western Kentucky coal production (power plants have begun buying western Kentucky coal again after installing scrubbers to address its high sulfur content). The tax reached all-time highs of $296 million in 2011 and $298 million in 2012. But by 2013, cheap and abundant natural gas was winning out over expensive-to-mine eastern Kentucky coal, and coal severance tax revenue fell to only $197 million by 2014.

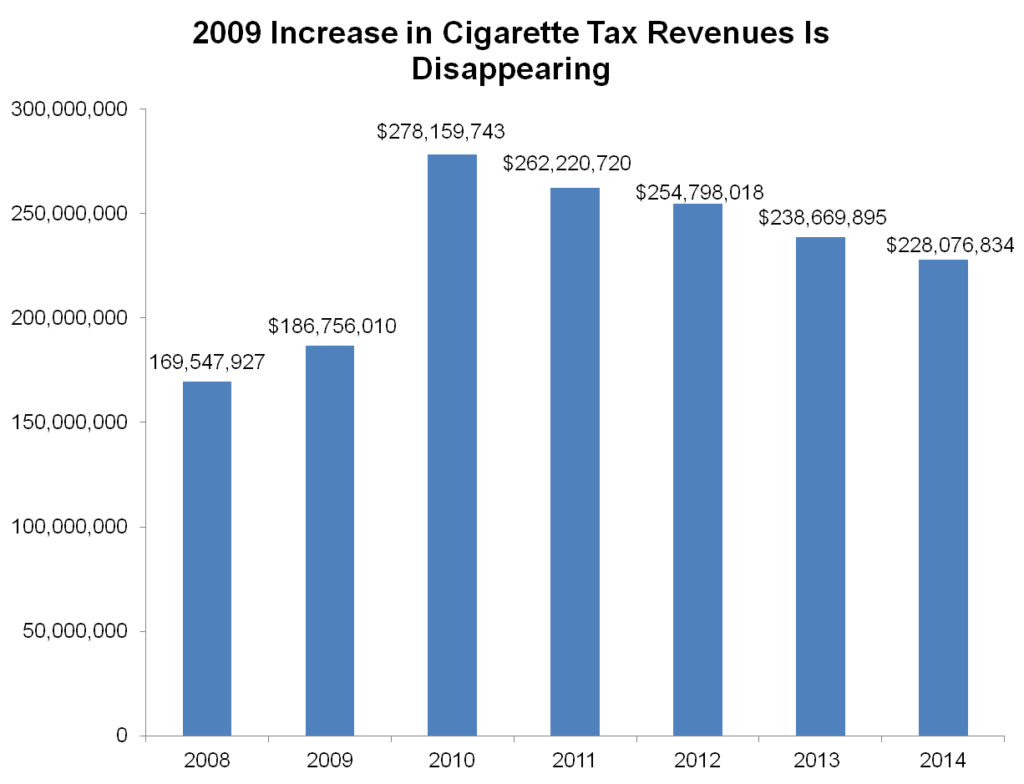

Cigarette tax revenues have dropped substantially.

Kentucky raised its cigarette tax in the 2009 session in order to help address the budget shortfall, resulting in $108 million more in 2010 than had been raised in 2008. But by 2014, the state had lost $50 million of that new revenue as declining smoking rates led to lower tax collections. While a cigarette tax increase is a good way to help curb smoking, it’s not a sustainable approach to the state’s revenue problems.

Source: KCEP analysis of Office of the State Budget Director data.

Source: KCEP analysis of Office of the State Budget Director data.

Moving forward, the combination of factors that led to strong revenue growth early in the recovery is unlikely to return. No one expects eastern Kentucky coal to regain its former strength, cigarette tax revenue will continue to decline, tax amnesty can’t be repeated and corporate profits are unlikely to continue at all-time highs. A stronger recovery would help the income tax and sales tax, but because of too many holes in the tax code Kentucky is likely to continue experiencing challenges until it takes on tax reform that raises more revenue.