A new version of the nation’s primary agriculture law known as the Farm Bill is making its way through Congress right now, and includes new provisions that would make it harder for some Kentuckians to receive food assistance. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) currently helps around 640,000 low-income Kentuckians with their grocery bills each month, and is a part of the Farm Bill. The policy changes to SNAP would cut food assistance by $17 billion across the nation and could result in tens of thousands of Kentuckians losing this assistance, harming families and the state’s economy where Kentucky grocers receive nearly $1 billion per year in SNAP spending.

Stricter work requirements in Farm Bill

Currently, non-disabled adults up to 49 years old who do not have children under 18 must work, or do some form of job training, for 20 hours per week in order to receive SNAP. This requirement, though misguided, has been in effect since the 1996 welfare reform law and since then states have been tracking compliance. The Farm Bill would expand this requirement in several ways. It would raise the upper age limit to 59 years old and exempt parents only if their children are under 6 years old. According to Census data, nearly 45,000 non-disabled Kentuckians aged 50-59 used SNAP at some point in 2016.

The proposal would also make it easier to lose and harder to regain SNAP benefits. Currently, SNAP participants have up to 3 months in any 36-month period of time that they can continue to use food assistance even if they don’t meet the work requirement. Furthermore, they can reinstate benefits by meeting the requirements at any time. The new law would require participants to prove on a monthly basis (down from 6 months) that they meet the 20 hour per week requirement and would lock them out of benefits for 12 months the first month they fail to meet the requirement. Each subsequent failure would result in a 3-year lock out of SNAP. For people already struggling to make ends meet, taking away food assistance for even a short time could be devastating, let alone three years of food insecurity.

Many who will lose SNAP already work, or struggle to do so in depressed local economies

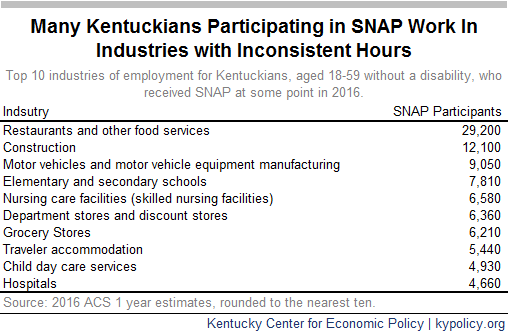

Many SNAP participants already work, but in industries that do not have consistent schedules and therefore vary in the number of hours employees work from month to month. These hours typically cannot be controlled by workers, who are sometimes given little notice of how many hours they are given in a week. The low wages, difficult working conditions, lack of paid sick leave and other challenges with these jobs contribute to high turnover, leading to periods of fewer hours worked. To punish a low-income worker by revoking food assistance for up to three years because a restaurant or construction worker could not work 20 hours per week one month is extreme and potentially dangerous.

SNAP participants in parts of the state where local economies have not yet recovered from the Great Recession or that face persistent job deficits, may struggle to find employment sufficient to keep SNAP benefits under the Farm Bill proposal. Of Kentucky’s 120 counties, 50 are or contain “labor surplus areas” as defined by the U.S. Department of Labor, indicating there are more people looking for work in that county or city than there are available jobs. While states can acknowledge this economic reality by waiving the existing work requirement, Kentucky is currently letting all but eight waivers expire—forcing the requirement to apply to parts of the state where it never has before. While Kentuckians (and local economies) from every corner of the commonwealth benefit from SNAP, the map below shows that usage is higher in economically distressed eastern and far western Kentucky.

Work requirements will not promote stable connection to the labor market for people who are already working but in unsteady jobs, or for those living in regions facing deeper economic challenges. Although work requirements have been used for 20 years now in SNAP, they are a policy that has not reduced poverty or improved employment among participants. Research has shown that it could even worsen deep poverty (an individual living at or below $6,070 per year, for example). There is also not evidence that SNAP is a deterrent to employment as work rates have continued to climb among SNAP participants, regardless of whether or not a work requirement was in effect.

In addition to the strictness of the proposed new work rules resulting in people losing SNAP benefits, the extensive new administrative requirements associated with the rules are likely to contribute to more benefit losses. Paperwork glitches and the difficulty of obtaining the needed documentation for people who sometimes work multiple low-wage jobs is likely to be a tripwire for many, especially since failure to meet reporting requirements on time even once can result in the previously-mentioned lockout.

Farm Bill rolls back state flexibility and requires unworkable tracking bureaucracies

States currently have some level of flexibility in how they determine SNAP eligibility and track participants, but the proposed Farm Bill would require new tracking that is expensive and would likely lead to fewer people with food assistance.

Currently, most states, including Kentucky, collect information related to SNAP participants’ work hours every six months to ensure they maintain eligibility. This requirement was designed ease the burden of tracking work requirements on states through the bipartisan 2002 Farm Bill. Kentucky does not currently have the capacity to receive, sort through and confirm paperwork confirming employment and hours for an estimated 157,000 adults on the proposed monthly basis.

Kentuckians are eligible for SNAP if their income and assets fall below a certain threshold. But the Farm Bill would restrict how states can determine eligibility by rolling back aspects of what is called “categorical eligibility,” which is a streamlined determination process that reduces the administrative burden of verifying applicants’ assets. Other changes could make it difficult for some families to qualify if they own a family vehicle worth more than $12,000 or use the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), and by imposing what is called a gross income test.

SNAP is efficient and helps local economies during downturns

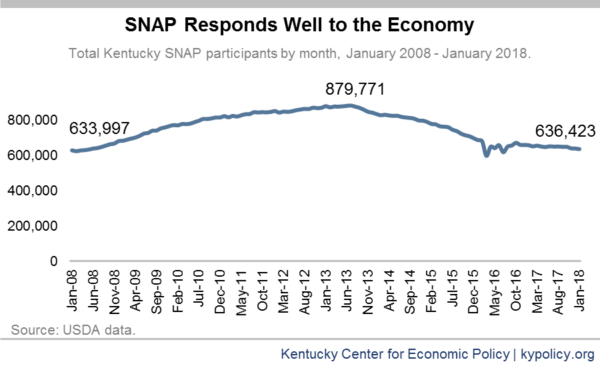

SNAP is an especially efficient program when it comes to providing assistance to those who need it and helping to alleviate the harm caused by a depressed labor market. As of January 2018, 639,423 Kentuckians used SNAP to help with their grocery bills, which is a 28 percent decline from its peak in July of 2013 and the lowest it has been since May of 2008. This caseload decline can largely be attributed to a slowly improving job market and modest increases in wages.

This swell in participation during downturns significantly smooths out the effects of economic hardship for both individuals and local economies. In 2013, SNAP pumped $1.3 billion into Kentucky’s economy. Even though participation has fallen since then, in 2017 SNAP was still responsible for $944 million in grocery and convenience store sales across the commonwealth. That money generates $1.70 in economic activity for every $1 spent through SNAP.

The SNAP provisions in the Farm Bill would almost certainly reduce enrollment, hampering the countercyclical effect of SNAP on our economy, cutting off a lifeline to still struggling communities and hurting thousands of families’ ability to make ends meet.