Since 2014, the federal financial assistance for out-of-pocket health care costs known as Cost Sharing Reductions (CSRs) has been under threat – first from a lawsuit filed by the House of Representatives, and now by threats from President Donald Trump to stop paying for it. In either case, ending those payments would hurt middle-class families who purchase insurance through the exchanges, destabilize the insurance market and raise costs for the federal government.

What are CSRs and how do they work?

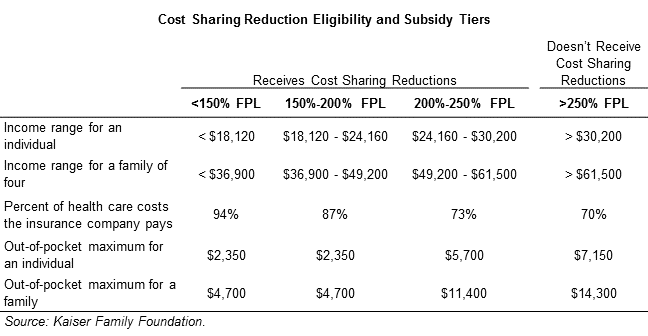

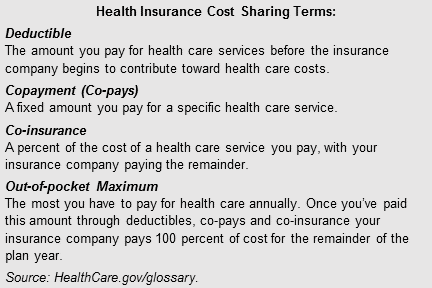

CSRs help low-income people use the insurance they purchase on the marketplace, thereby accessing the regular care they need to address conditions and improve health. Through CSRs, consumers who purchase coverage through the exchanges can receive help paying for out-of-pocket costs like deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance. Insurance customers are eligible for CSRs if they earn below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and select a silver-level insurance plan on the marketplace. The amount of out-of-pocket costs the CSRs cover depends on the income of the consumer, as shown in the table below.

For example, silver level plans, which are more generous than bronze plans and less generous than gold, normally require the enrollee to cover 30 percent of their health care costs and the insurance company pays 70 percent. But, if an enrollee earns less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) the enrollee only has to cover 6 percent of the after-premium health care costs associated with a silver plan and the insurance company pays 94 percent. This percentage of health care costs insurers must pay is known as the actuarial value of a plan.

Insurance companies can configure the out-of-pocket costs any way they choose through increasing or decreasing deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance as long as the total doesn’t exceed the actuarial value or a specific out-of-pocket maximum. The federal government then reimburses insurance companies for the added expense they incur.

How many Kentuckians get CSRs?

Just over half of Kentuckians who bought insurance through the marketplace qualified for and chose a plan with CSRs during the 2017 open enrollment period, according to HealthCare.gov data. However, 71 percent of silver plan enrollees, or 41,209, received CSRs. Among those, approximately:

- 21 percent earned below 150 percent of FPL.

- 49 percent earned between 150 and 200 percent of FPL.

- 30 percent earned between 200 and 250 percent of FPL.

While people in every county in Kentucky receive a cost sharing reduction, perhaps unsurprisingly the poorer parts of the state receive a larger share of the CSRs. In Elliott, Magoffin, Leslie, Clay and Rockcastle counties, over 70 percent of marketplace enrollees receive help paying for out-of-pocket costs. Here is the number and percent of marketplace enrollees with a CSR in each county:

What would it mean if CSR payments to insurers were cut off?

Insurers who sell plans on the marketplace are required to offer CSRs regardless of whether the federal government reimburses them for the added expense of paying an increased share of health care costs. So if the President decides to cut off those payments or the court decides against the legality of CSR payments to insurers, the result would be an unstable individual insurance market in the short term, more expensive plans for people who earn too much for premium subsidies and increased cost for the federal government.

Insurers would raise premiums or exit the marketplace altogether

Because insurers would still have to offer the CSRs to qualifying enrollees, without receiving federal payments, insurers would make up the added cost by raising premiums. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that if the CSR payments are not made, nationally, silver plan premiums would rise 20 percent in 2018 and 25 percent in 2020 and afterward. More specifically for Kentucky, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that in states that expanded Medicaid, insurers would have to raise premiums by 15 percent. The threat of lost CSRs is already being reflected in insurance companies’ rate filings for 2018, which have started to factor in a premium increase to compensate for the potential of losing CSR payments.

Some insurers, however, would likely decide to no longer participate in the exchanges and exit them altogether. In fact, according to a joint letter from health groups to Congress — including America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), the health insurance industry association — some insurance companies are already deciding to exit the marketplaces because of uncertainty around the CSR payments. The CBO estimates that in 2018 and 2020, approximately five percent of the country’s population would live in counties without any insurers. In Kentucky, Anthem stated explicitly in its rate filing justification that if the CSR payments are not made, they too may raise rates or exit Kentucky’s marketplace.

People who earn too much for the subsidies would feel premium increases the most

Because people who earn up to 400 percent FPL ($48,320 for an individual) receive premium tax credits that tie the cost of premiums to a percentage of their incomes, if an insurance company were to raise premiums, they would not be affected. In Kentucky there are 18,168 people covered through the marketplace who did not receive financial assistance to help pay for premiums — most often because their incomes were too high to qualify. It is for these people that a premium rate increase would be most harmful; they would be completely unshielded from escalating premiums due to non-payment of the CSRs. According to CBO, the average premium in 2026 for someone earning 450 percent FPL ($68,200) would be substantially higher than if the CSR payments were made:

- $1,300 more for a 21 year old

- $1,700 more for a 40 year old

- $3,900 more for a 64 year old

For this group, CBO believes they would almost entirely stop using the marketplaces to purchase insurance because they could find less expensive options off the exchange.

It would be more expensive to stop making CSR payments

Initially, it may seem intuitive that ending payments for the CSRs would save the federal government money, but in reality the federal government will be paying for it one way or the other. Because insurance companies would likely pass off the cost of providing CSRs, which is roughly $7 billion per year, through higher premiums for everyone on the exchanges, the federal government would subsequently increase the amount it pays for premium subsidies. This means even if it stopped making CSR payments, the federal government would still be paying for CSRs through enrollees who qualify for premium tax credits. The CBO estimates that between 2018 and 2027 the federal government would pay $118 billion less in CSR payments but have to increase its spending on premium assistance by $365 billion. Along with other budgetary effects, ending the CSR payments would cost the country $194 billion more over 10 years.

Congress should act to stabilize the individual market

The law specifies insurers are due the payments to cover CSRs, and insurers must provide CSRs regardless of payment. Due to a flaw in the statutory language, however, there is still a question about the legality of paying insurance companies for the CSRs they are providing (which is the basis of the lawsuit currently being litigated). Congress can and should explicitly appropriate those funds. As it stands, the Trump administration has near complete discretion as to whether or not to make the payments, but low-income insurance customers shouldn’t have to face premium hikes set on that uncertainty. Without Congressional action, Kentuckians may be needlessly harmed by the uncertainty around these payments. The CSRs are integral to providing usable coverage for low-income Kentuckians, and choosing not to pay for them is a lose-lose proposition.