The Official Poverty Measure is used to determine who can get medical, food, childcare and other forms of assistance. But the federal agency responsible for setting that measure is trying to alter it in a way that will make it harder for Kentuckians to participate in assistance programs and make ends meet.

At issue is that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) wants to start calculating poverty using a measure of inflation known as the chained Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (chained CPI-U), which grows more slowly than the one we currently use, the CPI-U.

This change would slowly cut the benefits Kentuckians receive. Although there wouldn’t be a dramatic effect right away (the chained CPI only grew 0.1 to 0.6 of a percentage point slower than the CPI-U between 2000 and 2017) the cumulative effect over time would harm many Kentuckians struggling to get by. For example, the Urban Institute estimated that if the chained CPI-U had been used to adjust the poverty measure for the past 15 years, 4,000 fewer Kentuckians would get help with their groceries through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

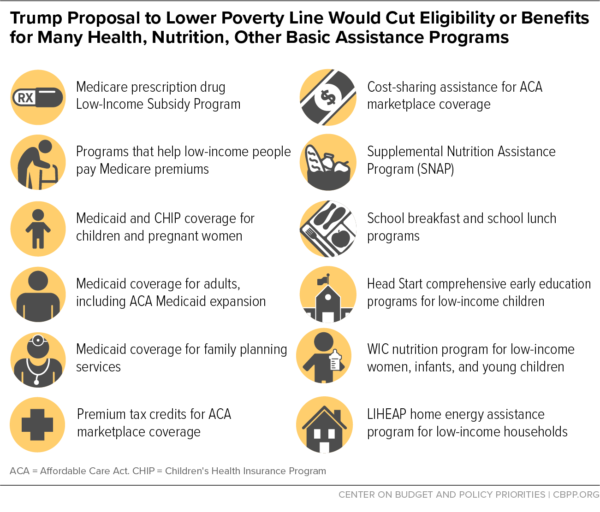

Ultimately, tens of thousands of low-income and disabled Kentuckians (including older Kentuckians and children) would either lose their assistance or see the amount of assistance shrink if the chained CPI-U were used to determine eligibility for these programs. The list of programs is long, and many Kentuckians utilize one or more of them at some point in their lives.

The federal poverty line is already modest. It was established in the 1960s using a method that fails to reflect the much-higher cost people face today for expenses like housing, childcare and healthcare. Today’s income levels are very low – only $12,490 per year for an individual and $24,750 for a family of four. This is roughly a third of what is needed for a modest but secure livelihood in Elizabethtown, for example, in a household of four.

The federal poverty line is already modest. It was established in the 1960s using a method that fails to reflect the much-higher cost people face today for expenses like housing, childcare and healthcare. Today’s income levels are very low – only $12,490 per year for an individual and $24,750 for a family of four. This is roughly a third of what is needed for a modest but secure livelihood in Elizabethtown, for example, in a household of four.

Even as OMB wants to reduce the poverty measure and make it harder for families to get assistance, we’re not making it any easier for Kentuckians with low-wage jobs to get ahead. This week marks the longest the U.S. (and Kentucky for that matter) has gone without raising the minimum wage – stuck at $7.25 an hour since 2009 ($2.13 an hour for tipped workers). Even at full-time, year-round work on minimum wages, a one-parent, one-child household falls below the current poverty line, for instance. Wages at and below the median have been substantively flat in real dollars for the last couple of decades, too.

At the state level, we have been scaling back our public investments in higher education, weakening the safety net by bringing back time limits for some adults with SNAP, and threatening unprecedented barriers to coverage for Kentuckians covered by Medicaid. This change to the way we measure poverty is yet another barrier preventing Kentuckians from getting on their feet and getting ahead.