House Bill (HB) 95 was signed by the governor and will provide much-needed help to reduce insulin costs for some of the 474,456 Kentuckians with diabetes, roughly 1 in 7 adults in the commonwealth beginning January 1, 2022. Under the bill, sponsored by Representative Danny Bentley, cost sharing for insulin will not exceed $30 per 30-day supply of any kind of insulin. By improving insulin affordability, the legislation will especially help low-income Kentuckians who would otherwise struggle to purchase needed medication.

Health coverage is expensive; insulin is very expensive

Although insulin is a very commonly prescribed medication, insulin prices have been growing rapidly in recent years, and are out of reach for many people with diabetes. Between 2012 and 2016, insulin prices at the point of sale more than doubled in Kentucky, growing from $352 to $721 for a 30-day supply. More recent national insulin cost data from Medicare shows the increase in pricing continued into 2019. This rapid growth is happening across the nation due to market conditions in the pharmaceutical industry such as minimal competition among insulin manufacturers (there are only three in the U.S.). Other factors contributing to the high cost of a very old medication are a very complex pricing system that obscures the price-setting process, the use of patents to shield relatively old drug formulations from lower-cost generics through incremental changes and the fact that the United States does not meaningfully regulate or negotiate drug prices.

The rising cost of insulin and inconsistent out-of-pocket costs have forced many to ration diabetes-related medicines or otherwise fail to take them as prescribed. Research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that roughly 1 in 7 adults under 65 who are diagnosed with diabetes skipped doses, took less of their diabetes medicine or delayed filling a prescription in order to save on costs. This rationing can create costly complications and consequences for health including an increased risk for kidney disease, blindness, loss of limbs, even death and most recently, severe illness from COVID-19.

HB 95 will lower out-of-pocket costs and keep them steady month-to-month — both important factors in affordability — for private health insurance plans. This includes employer-sponsored health coverage (except for self-insured plans, which comprise 63.5% of covered workers in Kentucky) and non-group coverage such as plans sold on the health insurance exchange. Combined, this is approximately 690,000 Kentuckians according to 2019 Census data.1 It is unclear how many of these Kentuckians have diabetes and need to purchase insulin.

Nearly 1 in 3 covered workers in Kentucky have health plans that require large cost-sharing on behalf of the insured — a number that has grown consistently over the past 15 years. And most plans on the health insurance exchange also have high cost sharing. Already, Kentuckians pay more out-of-pocket for health care than the U.S. on average, both in total cost and as a share of income, and Americans pay far more for prescriptions than others in advanced countries around the world – often as much as five to ten times more.

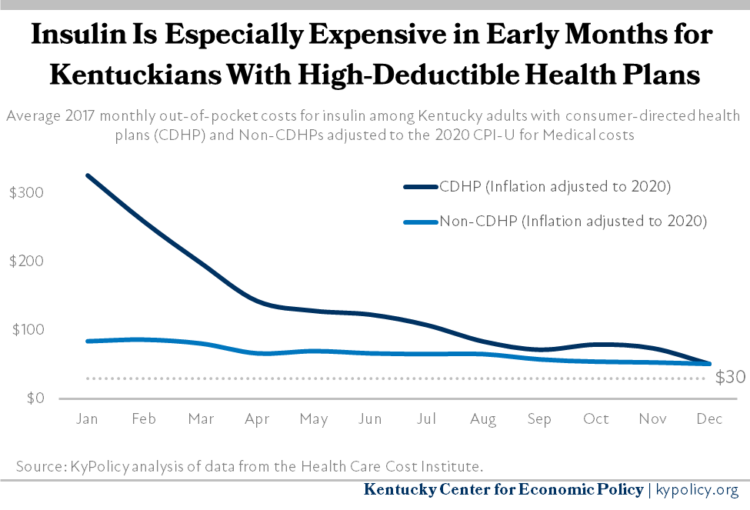

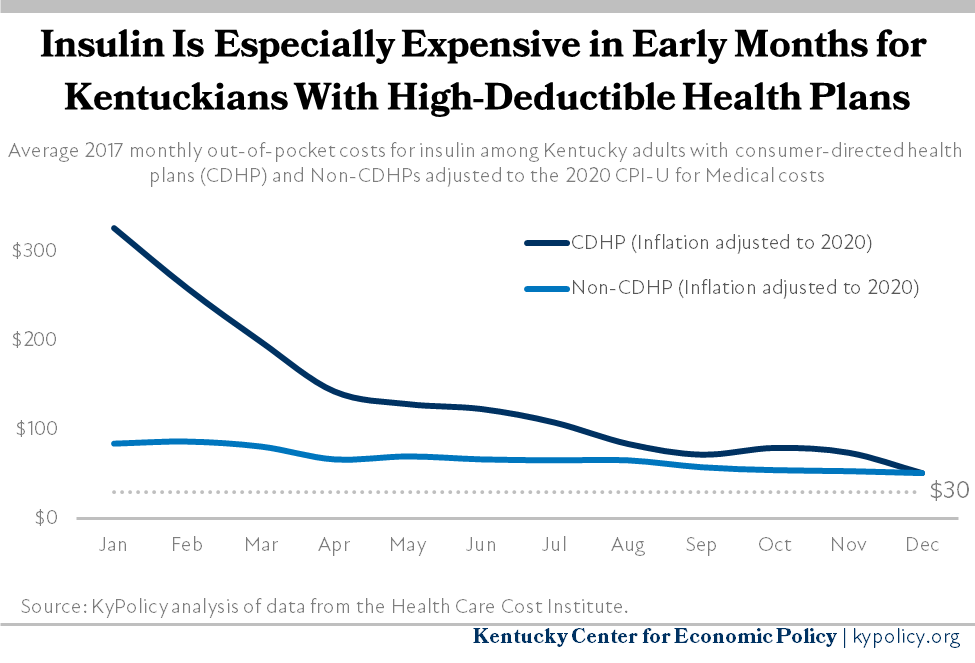

Privately insured Kentuckians who purchase insulin pay some share of the price at the pharmacy because their insurance requires them to meet a deductible, pay a co-pay, cover a fixed percentage of the cost through co-insurance, or some combination of these. Often, patients’ share of the cost is higher at the beginning of the year, when their deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums have not been met, and lower toward the end of the year. This is especially true for the 29% of insured adults who have health plans with high deductibles (as is often the case in what are called consumer-driven health plans or CDHP), who paid $138 per month out-of-pocket on average for insulin in 2017 (when adjusted to 2020 dollars), more than double what other covered adults spent that year on insulin ($69).

Capping monthly insulin out-of-pocket costs at $30 for Kentuckians with private health insurance will dramatically lower out-of-pocket costs for Kentuckians with high deductible plans. Their costs would drop by 78% on average, and other covered Kentuckians would see insulin costs fall by over half. This estimate probably understates how much HB 95 will save Kentuckians in 2021 as insulin prices (and therefore out-of-pocket costs) have very likely increased since 2017, the most recent year data is available.

Capping insulin costs will improve health equity and reduce economic toll of diabetes

Kentucky has the 5th-highest mortality rate due to diabetes in the nation. In addition to the 474,456 Kentuckians with diagnosed diabetes (the 8th-highest incidence rate of diabetes among states), it is estimated that an additional 198,052 adults have diabetes but their condition is undiagnosed. Due to health inequities caused by structural barriers to well-being, Black Kentuckians face higher rates of both prevalence (14.5%) and mortality (37.9 per 100,000) from diabetes than white Kentuckians (13.3% and 19.7 per 100,000 respectively) according to the Kentucky Minority Health Status Report. And due to economic inequities caused by those same barriers, Black Kentuckians are paid $0.82 for every $1 a white Kentuckian earns, making the costs of prescription drugs a greater burden. HB 95 is a step toward health equity in the commonwealth by reducing insulin costs for the disproportionate share of Black Kentuckians with diabetes, who are also underpaid by comparison.

Making routine care for diabetes more affordable is good for the Kentucky economy, too. In 2017, Kentuckians spent an estimated $367.8 million on over 10,000 hospitalizations due to diabetes. Diabetes-related hospitalizations are the 3rd most expensive among chronic diseases in Kentucky. But the overall economic cost of diabetes in Kentucky is far higher — $5.2 billion in medical costs, lost wages, lower productivity and other direct and indirect economic factors as of 2017. Lowering the out-of-pocket cost of insulin is critical to ensure Kentuckians don’t skip treatments, and can still afford other basic needs.

Updated on March 23, 2021.

- According to the American Community Survey 2019 1 year estimate for Kentucky, there are 1,425,500 Kentuckians who don’t work in government or the military and receive health insurance solely through an employer. Of those, 63.5% are in a self-insured employer plan, which is not subject to the cap, leaving approximately 520,300 who would be protected by the cap. Additionally, there are an estimated 169,600 Kentuckians covered by non-group insurance, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s analysis of the same data, who would be subject to the cap.