The drumbeat about a “crisis” in Kentucky’s pension systems over the last year included claims the state’s retiree health plans are also in trouble. But those systems are far better funded than most all other such plans around the country. While a majority of states have saved little-to-nothing for retiree health, Kentucky and its localities have set aside nearly $6 billion. Yet state decisions will force another big hike in health contributions starting in July, putting an even greater strain on state and local services.

Pre-funding retiree health benefits, as Kentucky does, is not common

Many states have long provided retiree health benefits to employees as a way to help attract and retain a qualified public workforce. But the option of pre-funding such benefits — meaning setting aside money ahead of time to earn investment returns as opposed to funding the benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis — is a relatively new idea. Only in the mid-2000s did the Governmental Accounting Standards Board create a rule for states to include an estimate of retiree health care liabilities in their financial statements.

Many states continue to make the practical choice of paying benefits directly rather than pre-funding them (the latter was not required by the accounting rule). States do that for a few reasons. Moving from pay-as-you-go to pre-funding means the current generation bears the burden of transition costs for prior generations that were not pre-funded. Second, pre-funding the benefits means estimating the future growth of health care costs. Those estimates are based on part on the unsustainably high health inflation rates of the past, meaning large contributions must be made that could prove unneeded over time.

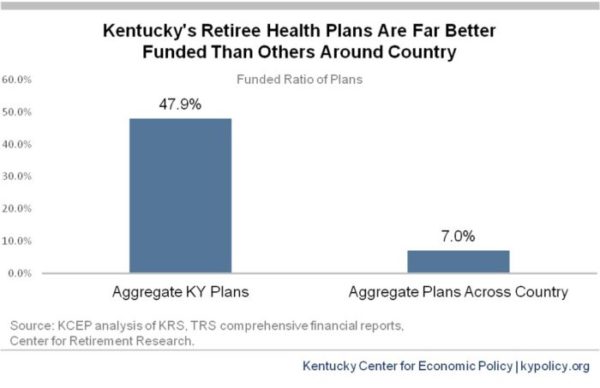

U.S. state and local retiree health plans as a whole are only seven percent funded in the aggregate, and about half of states have put aside nothing. In contrast, Kentucky’s plans are a much higher 48 percent funded, as shown in the graph below.

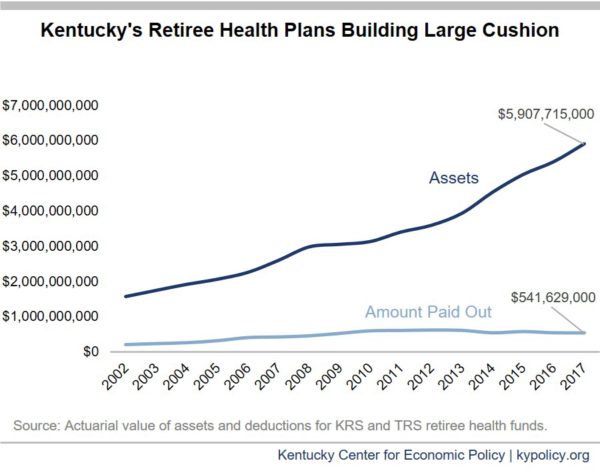

Kentucky has built a large cushion in retiree health, but is forcing itself to pay even more

The state’s pre-funding of these plans has resulted in a large balance of $5.9 billion across plans that is growing much faster than what Kentucky is actually paying in retiree health benefits and system administrative expenses. Assets are climbing rapidly, while what is being paid out in benefits and costs has been relatively stable, as shown in the graph below.

Despite Kentucky already having built a strong cushion not required of retiree health plans, contributions are spiking up again next year. That’s because of sudden assumption changes made by the Kentucky Retirement Systems (KRS) board. Starting in July, contributions to the retiree health plans of the Kentucky Employees Retirement System (KERS) non-hazardous system will jump 49 percent and to the State Police Retirement System 45 percent. Payments to the County Employees Retirement System retiree health plans will also go up, though increases are capped at 12 percent a year by legislation passed to phase-in the harm to localities from the KRS board decision.

What’s more, the sewage-to-pension bill now declared unconstitutional by the Franklin Circuit Court would’ve required KRS employees hired between 2003 and 2008 to sacrifice one percent more of their salaries toward the retiree health funds. That included KERS hazardous employees whose retiree health plan is already 118 percent funded.

Kentucky’s difficulty paying retirement system costs is being stoked by exaggerated claims not based in fact — like claims of a crisis in our retiree health plans. We need a more commonsense approach to funding. That means fully protecting the benefits of underpaid public employees and teachers while easing the pressure on state and local governments from a manufactured crisis of unnecessarily high contributions.