Those arguing for a shift toward sales taxes and away from income taxes in Kentucky overstate the influence of income taxes on where people live. And they overlook the benefits of income taxes, including how they improve tax fairness and drive long-term revenue growth.

One argument, which comes up in the consultants’ report to the governor’s tax reform commission, concerns location decisions along Kentucky’s border regions. Since close to half of the Kentucky population lives close to a state border, there are more opportunities for individuals to choose which state to live in. Yet while the research on this question finds that income taxes make a statistically significant difference in location choices when everything else is equal, the effect found is small.1 And everything else is rarely equal, as residents take into account differences in public services, amenities, lifestyle options and commutes in making location decisions.

Part of the reason the effect is small is that income tax rates don’t tell the whole story of how taxes differ between states. Those states with lower income taxes typically have higher property and sales taxes. Also, some states like Indiana, Illinois, Ohio and West Virginia don’t allow itemized deductions on their income taxes, making the difference in actual income taxes paid less than the tax rates would imply. And the federal deductibility of state income taxes has the effect of decreasing the real difference in income taxes between states. Many people get back 25-35 cents of each dollar they pay in state and local income taxes in lower federal income taxes.

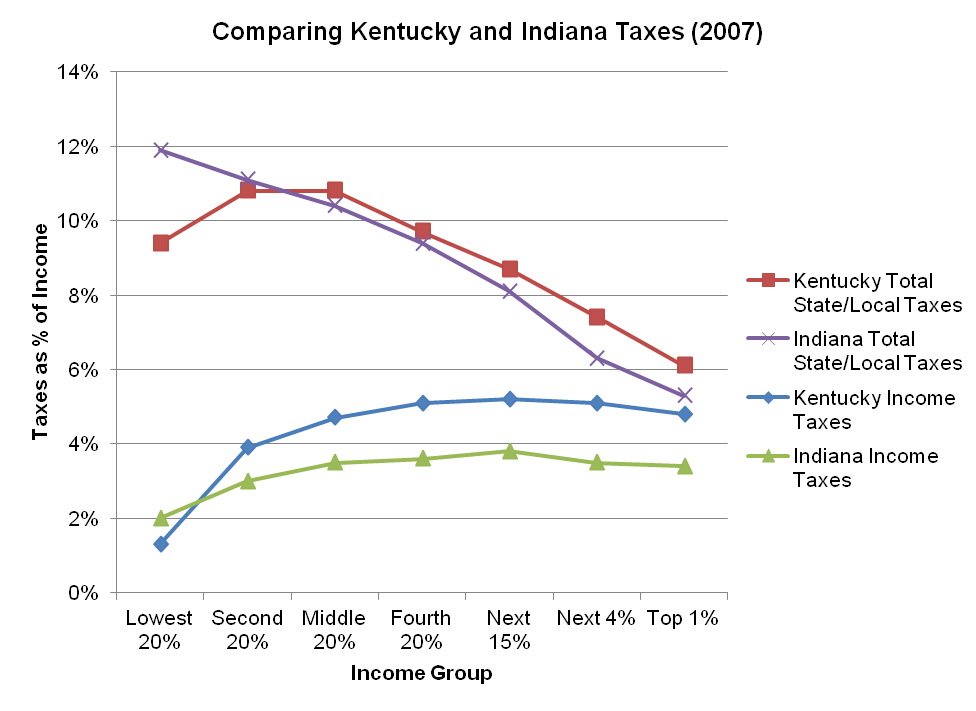

Below are two graphs illustrating the big picture of how Kentucky’s taxes compare. The first looks at Kentucky and Indiana. While it’s true that for many income groups Kentucky has higher income taxes (state and local) than Indiana, the difference between the two states shrinks when all state and local taxes are compared.

It’s also clear from the graph that Indiana’s tax system is more regressive than Kentucky’s—Indiana taxes low-income people more and high-income people less. That’s what happens in states with tax systems more heavily weighted toward sales taxes than income taxes.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy2

The second chart looks at total state and local taxes by income group for Kentucky and all its surrounding states. As the graph shows, total tax systems in these states are actually very similar. The one real exception for high-income people is Tennessee, which has lower state and local taxes on the upper end because it lacks an income tax on non-investment income (Illinois has raised its income tax since this study was done). However, Tennessee pays for this omission with a very regressive tax system and among the lowest per student public school funding in the country.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy3

Focusing on income taxes alone ignores this broader context as well as other research that questions how much income taxes affect where people live. Cuts or increases in state income taxes do not lead to substantial in- or out-migration. One important reason is that few people move between states anyway (only 1.7 percent of US residents move on average annually). Those that move are largely motivated by factors other than taxes, including job opportunities, family considerations, housing costs and the weather. Tax differences between states are small when all taxes are taken into account, as shown above, and are especially small when compared to other differences like housing costs. And high earners are more likely to have many of the characteristics that discourage relocation, including marital and employment status, age, homeownership and community responsibilities.4

Also often overlooked is the important role of individual income taxes, as compared to other taxes, in generating adequate revenue needed for ongoing investment in public services. Income taxes grow faster than other taxes—in the long run, according to one analysis, income taxes can be expected to grow over twice as fast as sales taxes.5 This means “maintaining investments in education and infrastructure is more difficult as sales taxes become more dominant.”6

Kentucky already has a serious problem with long-term revenue growth. Any move away from income taxes would worsen that problem while shifting tax responsibility away from those most able to pay.

- See William Hoyt, et al., “Report to Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Tax Reform by Economic Consultants,” September 19, 2012, http://ltgovernor.ky.gov/taxreform/Documents/20120919/20120920_ConsultantReport.pdf, p. 38. ↩

- Share of family income for non-elderly taxpayers; includes impact of federal deduction offset. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” November 2009, http://www.itepnet.org/whopays.htm. ↩

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays?” ↩

- Robert Tannenwald, Jon Shure and Nicholas Johnson, “Tax Flight is a Myth: Higher State Taxes Bring More Revenue, Not More Migration,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 4, 2011, http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3556. ↩

- Donald Bruce, William F. Fox and M. H. Tuttle, “Tax Base Elasticities: A Multi-State Analysis of Long-Run and Short-Run Dynamics,” Southern Economic Journal, 2006. ↩

- Donald Bruce and William Fox, “Revenue Options for Ohio’s Future,” Report Prepared for the Education Tax Policy Institute, May 13, 2011, http://www.etpi-ohio.org/assets/Ohio-Tax-Structure-022211KEMfinallogo2.pdf. ↩