An article by the Bluegrass Institute (BIPPS), and a series of follow-ups on individual school districts, tell a grossly inaccurate story about public school spending in Kentucky. The apparent intention is to paint a picture of waste and failure at Kentucky public schools to get voters to support Amendment 2, which will shift tax dollars from public schools — where 90% of students attend — to private education.

The analysis attempts to obscure nearly 20 years of harmful state funding cuts to public education by falsely characterizing increased pension liability debt payments as spending on schools, using a misleading choice of comparison years to obscure nearly two decades of budget cuts, distorting spending on teachers, and counting one-time pandemic funding as if it was permanent.

In reality, eroding state funding for education since 2008 has led to a variety of harms, including lower inflation-adjusted teacher pay, a growing educator shortage, and cuts ranging from fewer days in the school calendar, reduced course offerings, increased fees and reduced student supports.

Article misrepresents pension liability contributions by counting them as education spending

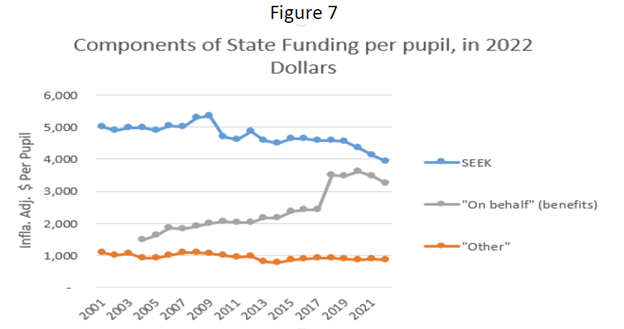

BIPPS treats the dramatically increased state pension contributions of recent years as an increase in funding for schools. But those are debt payments, not education spending. Yet BIPPS includes them in per pupil school spending to make those numbers look much larger than reality. Including these pension debt payments inflates state spending on P-12 schools by a massive 39% above actual levels.

Those increased costs are catch-up payments resulting from many years in which the legislature did not make the full actuarially determined contributions to the Teachers’ Retirement System, creating a large unfunded liability. Payments to reduce past unfunded liabilities do not go to schools, and therefore should not be considered education service delivery. They simply address unpaid debts of the commonwealth legally owed to past and current teachers.

These increased payments are also not associated with an increase in pension benefits offered to teachers; to the contrary, those benefits have declined in quality for newer cohorts of teachers over recent decades as the legislature has introduced four tiers based on date of hire, each with reduced pension benefits compared to earlier tiers. That has made it harder to attract and retain teachers, exacerbating the teacher shortage already made worse by state funding cuts.

Article’s choice of highlighted comparison years obscures when state funding problems began in earnest – in 2008

It has been widely understood that Kentucky was making progress in education funding immediately following the Kentucky Education Reform Act in 1990 and to some degree up until the Great Recession in 2008. Funding was not only keeping up with inflation but was regularly increased to address past inequities and make much-needed strides through new investment. That was the required result of the 1989 Rose decision that declared our state funding system unconstitutionally inadequate and inequitable.

But headlining a comparison of current spending to 1990, which is before additional dollars from KERA tax increases even began, implies continuous funding progress over that period, which is simply not the case.

Only upon close examination does data in the initial BIPPS article confirm that SEEK funding has declined in inflation-adjusted dollars since 2008, and that average real teacher pay also declined dollars over that period. It’s that last 18 years of funding (through the 2024-2026 budget) that are the concern for public education. Total SEEK funding is now an inflation-adjusted 26% less than it was in 2008.

The post-2008 story, with a real decline in SEEK funding and an increase in “on-behalf payments” for unfunded pension liabilities (and health insurance, as described below), is not highlighted in the topline story but is revealed in a graph on page 7 of BIPPS’ article, shown below.

Article misrepresents spending on teachers

The article contrasts what the author admits are teacher salaries that have not kept up with inflation with the claim that “hiring of non-teaching staff in schools has grown dramatically.” One way this claim is made is to show that total education funding has increased by 2.22 times since 1990 while average teacher salary has increased only 1.08 times. However:

- This comparison ignores the fact that the number of teachers has increased 21% since 1990 by the article’s own data, as if increased spending to hire more teachers does not have anything to do with teachers.

- It ignores the issue mentioned above by counting the large recent increases in unfunded pension liability payments as education spending, when in fact it is spending on debt.

- Health care costs have also grown dramatically since 1990 (much faster than general inflation) and were a growing share of compensation over this period for all private and public employers, but this fact is not mentioned and that aspect of total teacher compensation is not attributed to teacher-related spending.

Almost the entire increase in non-teaching staff the article identifies happened in the 1990s, some of which may be related to important improvements like the addition of Family Resource and Youth Service Center staff at schools, and some of which may be associated with increased requirements of state testing and reporting. Since 2002, the number of teaching staff has increased 7% and non-teaching staff by 1%, according to the article’s own data, meaning no trend away from teacher to non-teacher staffing over the last 20 years. And it is in this recent period, particularly since 2008, that teacher salaries have not kept up with inflation. This is another area where the comparison to 1990 is misleading in trying to understand the important funding declines of the last couple of decades.

Article counts but doesn’t mention that the recent increase in federal spending is temporary, expiring in 2024

To make recent per pupil spending appear inflated even further, BIPPS includes the recent $3 billion in emergency pandemic federal funding. But that money is expiring now and won’t be renewed.

According to the legislature’s Office of Education Accountability, a total of 3,890 school positions are funded across the state with those pandemic dollars through a program known as ESSER. Of those, 2,133 or 55% are existing positions for which other funding will have to be identified when the money runs out, or positions will have to be cut. Of the other 1,757 new positions created with ESSER funds, only 349 are expected to be retained when the monies end, meaning a loss of services that are currently being provided.