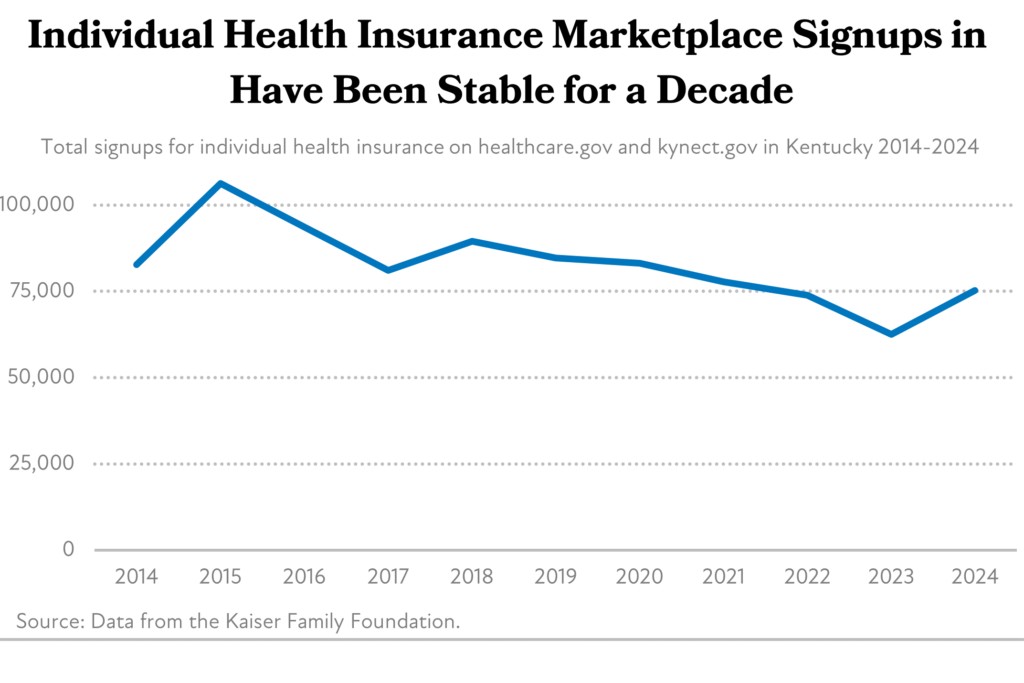

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) created several new opportunities for health coverage in Kentucky that began in 2014, including a marketplace where Kentuckians with low wages can receive subsidized insurance plans. A decade later that marketplace, known as kynect, covers over 75,000 Kentuckians, most of whom purchase coverage at a discounted price.

Recent federal legislation has made these health insurance subsidies more beneficial and opened them up to more people. But those improvements will expire next year without additional steps from Congress, putting the affordability and availability of life-saving health coverage for Kentuckians at risk. Further improvements to promote better health are also needed, especially when it comes to lowering the often high out-of-pocket costs that come with marketplace plans.

Kentucky’s health insurance marketplace has been effective at providing affordable coverage options on a consistent basis

The ACA brought about a national system of subsidies for health insurance premiums as well as the additional costs associated with using coverage, such as deductibles and copays. In Kentucky, 83% of those enrolled in a marketplace plan received a federally funded Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC) to help with premium costs during the 2024 open enrollment period. Approximately 39%, nearly all of whom were already receiving an APTC, received an additional subsidy called a Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) to reduce out-of-pocket costs. As a result, the average customer with an APTC paid $134 per month — in contrast to the average, unsubsidized premium of $621 a month — and more than 8,000 Kentuckians (11% of enrollees) had a premium of $10 or less.

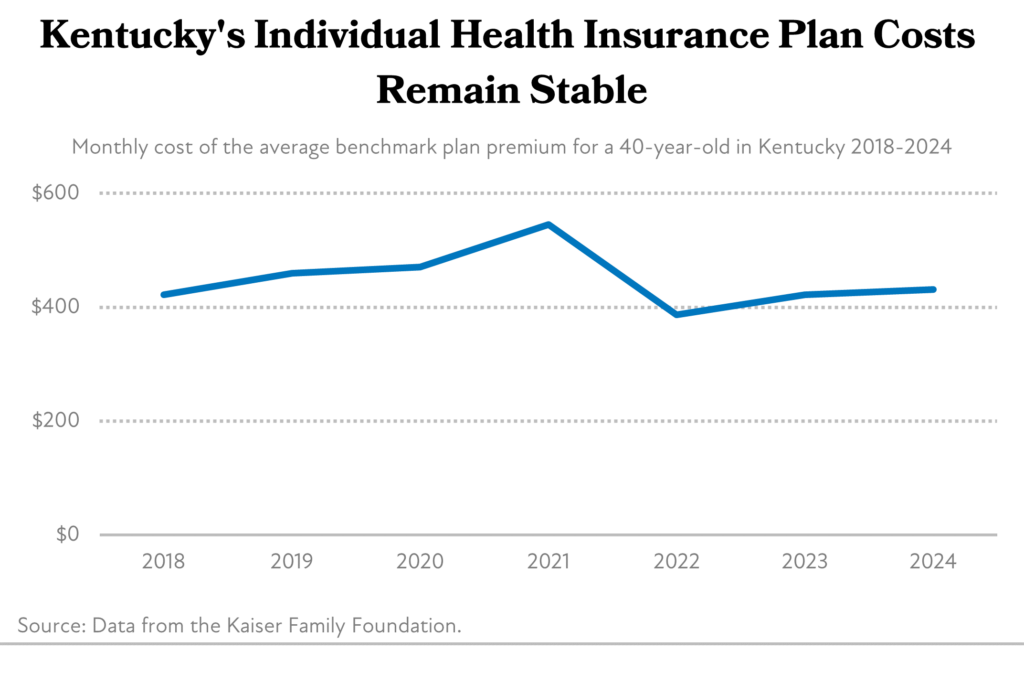

Premium amounts for Kentucky’s marketplace plans have been remarkably stable over the past decade, despite early concerns that the state’s health insurance marketplace was in a “death spiral,” where sick patients drive up costs that creates a vicious cycle of rising premium prices and fewer enrollees. The premium for a benchmark plan (the type of health coverage plan that the value of the APTCs is based on) has not grown substantially over the past several years. Health insurance premium costs remained stable for plans during the 2024 open enrollment period, varying from -2.2% (Molina) to +11.5% (CareSource) compared to last year’s price.

Participation in these plans has remained stable as well. After an initial increase in 2015, marketplace participation declined for several reasons including an improving economy and a switch from kynect.gov to healthcare.gov. Then-Governor Bevin’s decision to give up the state-based marketplace (kynect) in favor of a federally-facilitated marketplace, which meant the state had less control over marketing, the length of time people can enroll (an “open enrollment period”), and the ability to check for eligibility alongside other assistance programs. Then, during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent downturn, Kentucky returned to a state-based marketplace, and the federal government required states to maintain Medicaid coverage for anyone who joined between January 2020 and March 2023. This resulted in a further decrease in marketplace participation, as many who would have signed up for a marketplace plan were already covered by Medicaid. However, when that mandate ended in 2023, the state began redetermining if Kentuckians were eligible for Medicaid and found that tens of thousands no longer qualified. Many of these Kentuckians then turned to the marketplace for coverage during the 2024 open enrollment period, resulting in the first increase in participation since 2018.

Recent improvements to federal subsidies have further lowered coverage costs and need to be made permanent

Following the implementation of the American Rescue Plan Act and Inflation Reduction Act, premium costs fell in 2022, because each law increased the value of the premium tax credits and expanded who was eligible for them. Specifically, these federal enhancements helped by:

- Lowering the caps on premium contributions for people of all income levels;

- Allowing people with incomes between 100% and 150% of the poverty level to pay $0 in premiums for “benchmark” silver-level plans; and

- Extending eligibility for APTCs to people with incomes above 400% of the poverty level if their benchmark premiums would exceed 8.5% of household income.

The expansion of the availability of premium subsidies was a particular leap forward in the ACA’s marketplace. Prior to 2021, only those with incomes up to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL, or $60,240 for an individual at 400%) could qualify, leaving out many middle-class working Kentuckians who were often self-employed or small business owners, and therefore didn’t have a health plan through work. But after the American Rescue Plan Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, those subsidies were available to ensure premiums remained below 8.5% of household income. Because of this improvement, 8% of enrollees earned at or above 400% FPL.

The enhanced APTCs have been especially important for low-wage-earning Kentuckians as well, as many who recently lost Medicaid coverage turned to the marketplace for their health coverage. The availability of additional premium assistance on the marketplace has been important in ensuring as few of these Kentuckians go uninsured as possible.

However, the most recent federal law that included the improved premium subsidies, the Inflation Reduction Act, sunsets these improvements by the end of 2025. Should that occur, it is primarily middle-class earners who will see the steepest rise in their premiums. For example, a family of four with a household income of $125,000 would see their premiums increase by 55%, or $5,911 annually. Congress should act soon to keep these improvements permanent.

Using Marketplace-purchased coverage is still too expensive

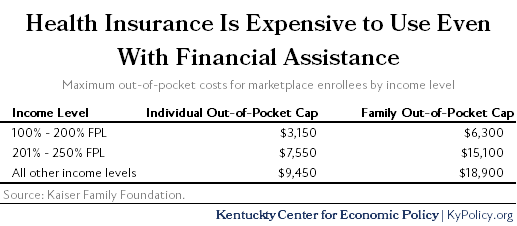

While the insurance subsidies available to Kentuckians through the marketplace have helped more Kentuckians afford coverage, it remains very expensive to use that coverage. For those with incomes low enough to qualify for CSRs (at or below 250% FPL, or $75,000 for a family of four), out-of-pocket costs like deductibles, co-pays and coinsurance are capped at a lower amount. But even with the help of CSRs, out-of-pocket costs are still expensive. For example, a family of four at 150% of FPL has an income of $45,000. At this income level, this family still has an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $6,300, meaning they could still spend up to 14% of their household income on medical costs.

In addition to extending the premium subsidies, lawmakers should tackle the high cost of using health insurance. A broad body of research shows that higher out-of-pocket costs reduce the use of important medical care, including vaccinations, prescribed medicines, mental health visits and preventative primary care, particularly among low-income patients. Higher cost sharing can even be associated with an increased likelihood of using the emergency room for non-emergency reasons, which is ultimately more costly and less effective. Reducing cost sharing by improving CSRs or by allowing more people to enroll in Medicaid would help alleviate these burdens and build on the successes that the marketplace plans have had over the past decade.