We don’t know yet the specifics of a tax reform plan the governor wants the General Assembly to consider in a 2017 special session. But this week, in a letter sent to legislators indicating the session will be held sometime after Aug. 15, the governor said Kentucky can become “more competitive with surrounding states like Indiana and Tennessee by lowering or eliminating certain taxes.” Given the makeup of those two states’ tax systems, this language suggests a potentially harmful direction that involves lowering taxes for the wealthy and corporations and a shift to greater reliance on taxes from low- and middle-income households.

Some features of Indiana and Tennessee’s tax codes the governor might be pointing to:

- Tennessee lacks a broad based individual income tax, and its tax on investment income was cut in 2016 and will be completely phased out by 2022. In recent years, Indiana has cut its individual income tax to 3.23 percent (Kentucky’s top rate is 6 percent).

- Tennessee got rid of its inheritance tax on wealthy heirs in 2016; Indiana did the same in 2013.

- Just this spring, Tennessee gave a $113 million business tax cut to manufacturers, and in 2012, Indiana started phasing in a reduction to the state’s flat corporate income tax rate, to conclude in 2022 at 4.8 percent (Kentucky’s top rate is 6 percent).

- Neither state taxes business inventory.

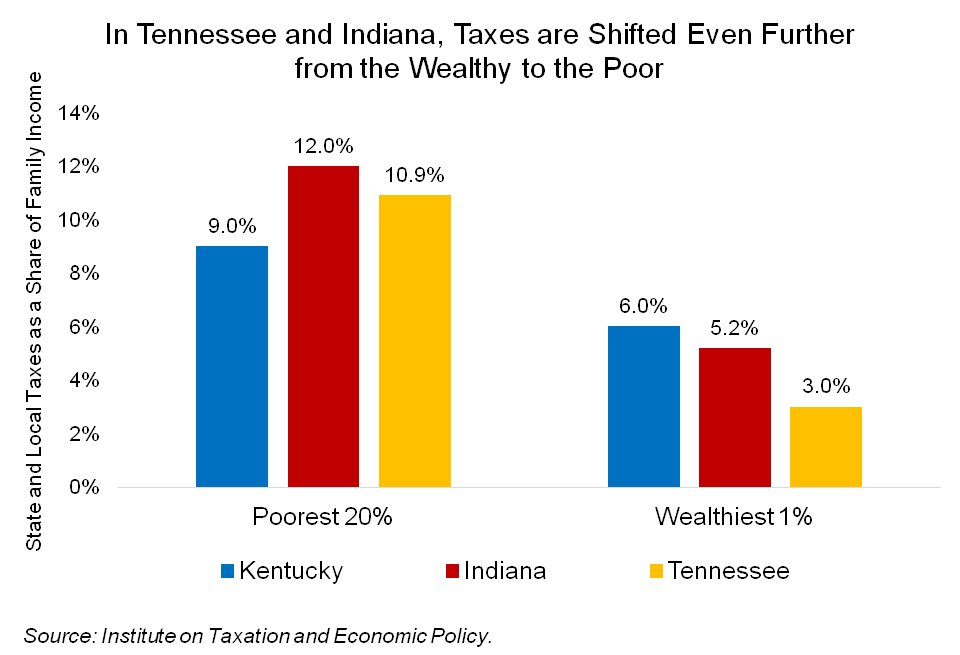

The corporate tax cuts described above mean profitable businesses chip in less for the public services that help them succeed. And the result of less reliance on income and inheritance taxes is clear (see graph below): those at the top in Tennessee and Indiana pay an even smaller share of their income in state and local taxes than the wealthiest Kentuckians do, and their lowest-income residents pay an even higher share than the poorest Kentuckians. Tennessee has the 7th-most regressive tax system of all 50 states and Indiana has the 10th-most regressive while Kentucky is ranked 33rd, according to a study by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Part of that heavier reliance on low-income Hoosiers and Volunteers is due to the higher sales tax rate in Tennessee and Indiana of 7 percent compared to Kentucky’s 6 percent rate (Tennessee also taxes groceries at 5 percent and has significant local sales taxes). Becoming more like these states by cutting taxes for the people at the top and relying more heavily on taxes from everyone else will make Kentucky’s system even more acutely upside-down than it already is, where those with the most pay the least in taxes of any income group.

Though Governor Bevin does say in his letter that he also wants to “[close] special-interest tax loopholes” (which constitutes real reform), lowering and eliminating taxes like those described above amounts to huge tax cuts for the powerful interests at the top. In other words, such an approach to changing our tax system could pile on, rather than clean up special interest tax breaks – holes in our tax system that are already draining revenue growth from our General Fund and leading to round after round of budget cuts and pension underfunding.

While the governor rightly stresses the need for “sufficient” revenue, he says “the best solution to Kentucky’s financial challenges is economic growth” which he implies will be generated through “competitive” tax changes. Other states that have attempted trickle-down tax cuts to generate private sector investment and hiring (and thus, more tax revenue), have found themselves instead facing lackluster economic growth and budget shortfalls in the hundreds of millions of dollars. The Kansas legislature just repudiated its failed experiment in reducing income taxes by rolling back those cuts and reinvesting in its schools and other public investments.

Taxing the poor more and the wealthy less like Tennessee and Indiana do is not going to solve Kentucky’s problems, if that’s where the governor is heading. What the commonwealth really needs is for leaders to prioritize investments in our state and communities above tax cuts for powerful interests.